By Kenley Alligood, UMFA membership manager

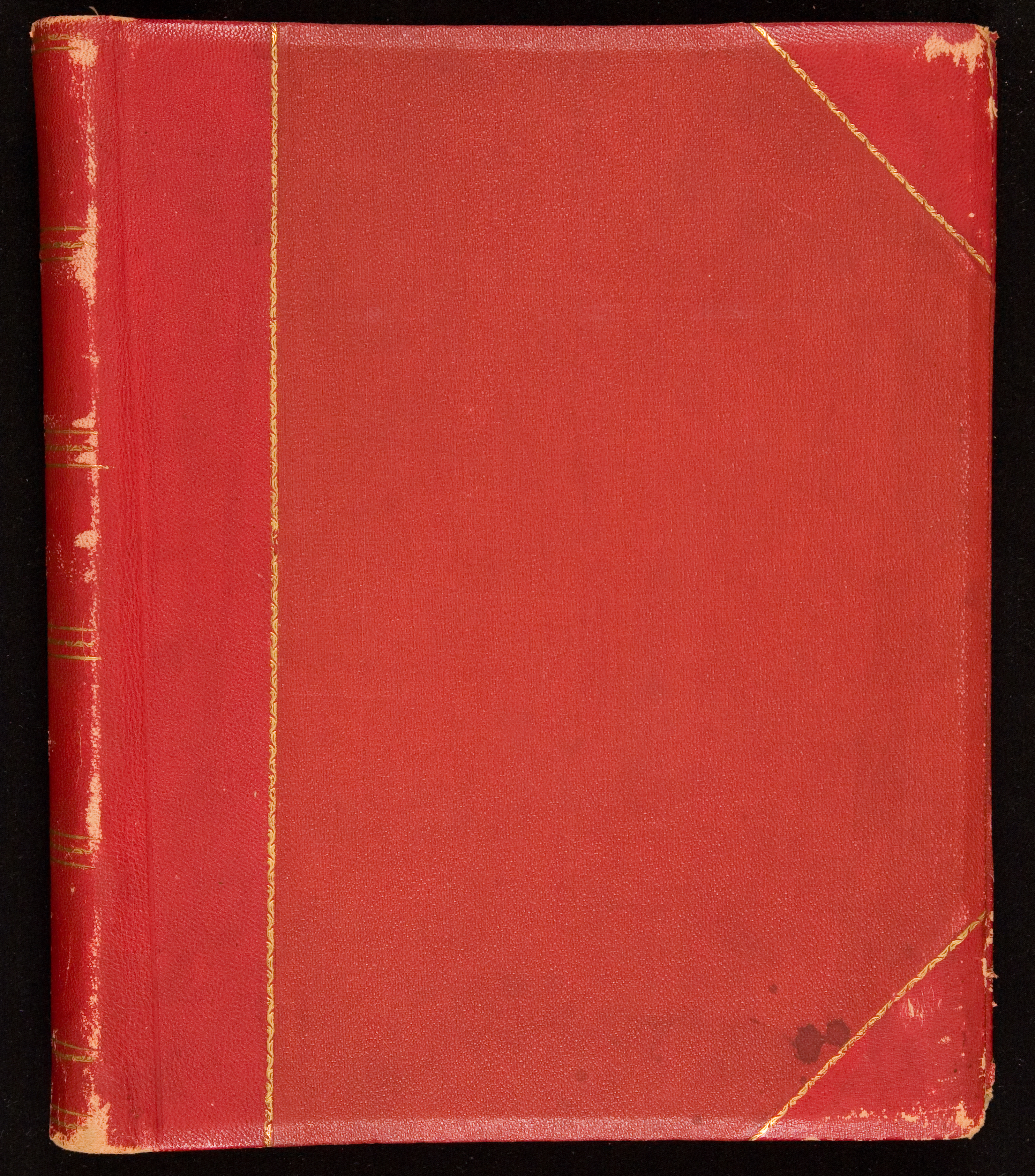

As the managing editor of the UMFA’s membership publication Quarterly, I spend a lot of time looking through the Museum’s permanent collection database for images. On this particular occasion, I was looking for a cover-image for the October/November/December ‘24 issue with the vague idea of “winter” hoping to gather a handful of potentials to take back to the design team. I had found a few that I thought might work when I saw it – the circa 1880s image of a group of people trekking across the surface of what is still the largest glacier in France, La Mer de Glace. The albumen print is one of many collected in a red, faux-leatherbound album by an individual known only as “the artist C.H. Turner.” The album itself made its way into the UMFA’s collection in 1999, and we know very little about the original owner or the images contained within, but they span continental Europe: Geneva, Zurich, Strasbourg, Rome, Frankfurt, Paris. This is a record of someone’s travels, captured on film.

The Mer de Glace, 2022.

Today, that fact is unremarkable. Photography is ubiquitous. We grew up with shelves of photo albums full of moments both significant and inane, moms who scrapbooked our family vacations and dutifully documented our first days of school, and disposable film cameras for the fieldtrip to the zoo. Now, the question is where to go to get film developed (does CVS still do that?), and why bother with fussy film when the device in my pocket can store thousands of images with ease? And yet the obsession with documenting our world and experiences, the special quality of photography to faithfully freeze a single moment in time, remains.

Which brings us back to why the UMFA’s red, leather-bound photo album is so special: it was a fairly new phenomenon. Cameras in the early 1800s were large, heavy, and the images were tedious to process. The average person was not hauling one around anywhere, but especially not on a jaunt through Europe. All of that changed forever with a company called Kodak and the 1888 release of their first hand-held camera. The Kodak cost $25 (just over $800 today) and came pre-loaded with 100 exposures on an internal film roll. When the roll was full, all the user had to do was pay the $2 fee to ship the camera back to the Kodak Eastman company offices in New York for development (i). Cameras were now easy, convenient, portable, and relatively affordable.

But our image pre-dates this, so how did it come about?

The Alps were a popular travel destination, particularly with British tourists, by the mid-18th century. Englishman William Windham recorded his 1741 travels to the region in a pamphlet titled An Account of the Glacieres or Ice Alps in Savoy in which he described a “Lake put in Agitation by a strong Wind, and frozen all at once”— the first known published description of what would come to be called the Mer de Glace. Windham’s group was one of the first to make the trek to the remote environs of Mount Blanc purely for pleasure, but they would not be the last. His account was instrumental in bringing scientists and tourists to the area in droves (ii). In the 1840s, a small stone structure, the Refuge de Montenvers, was built at the base of La Mer de Glace to house tourists and mountaineers. By the 1880s, increased interest in the glacier necessitated the construction of a larger and more luxurious building: the Grand Hotel du Montenvers, accessible from the valley by train.

The Grand Hotel du Montenvers, 2022.

Tourism, as we would define it today, is not a new phenomenon. Traveling about purely for pleasure and entertainment has been popular among those who could afford it since the 18th century in Europe (as evidenced by Mr. Windham’s adventures). But tourism, and the collecting of what we would call souvenirs, is much older. A good example of this comes to us through Geoffrey Chaucer’s remarkable Canterbury Tales which tells us that when April’s sweet showers arrive, “Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages” (Prologue, 12) (iii). This 14th century manuscript describes a practice already hundreds of years old in which people, common and high-born alike, took time away from their daily tasks to travel to sites of religious significance, often associated with the lives (and remains) of the saints. They came to see — and perhaps purchase — relics (teeth, disembodied hands, bodies incorruptible, pieces of the true cross, etc.), though even by Chaucer’s time there was a healthy trade in fakes, as evidenced by "The Pardoner’s Tale" in which the Pardoner proudly boasts of benefiting financially from the practice. (iv)

The idea of pilgrimage is of course much older than Chaucer and spans the globe and world religions, and over time the lines between the sacred and the secular have blurred. The places which hold deep significance for us these days are not always the graves of saints. Traveling to Dublin to gaze at the illuminated pages of the Book of Kells or the first copy of James Joyce’s Ulysses, or going to a concert at First Avenue in Minneapolis where Prince performed, are pilgrimages in their own way. And who among us doesn’t leave with some token of remembrance – a keychain, a t-shirt, a photograph?

The word ‘souvenir’ first entered the English lexicon at the end of the 18th century, in tandem with rising interest and participation in tourism. (v) But the term is retroactively applied by modern researchers and historians to describe mementos collected on a journey, for example the cheap metal badges Chaucer’s pilgrims could collect at Becket’s shrine at Canterbury. The rapid technological advancement of the camera, its increasing popularity and accessibility, and the ability to mass-produce images gave rise to a new type of souvenir: the photographic print.

In the essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Benjamin posits that “technical reproduction can put the copy of the original into situations which would be out of reach for the original itself. Above all, it enables the original to meet the beholder halfway, be it in the form of a photograph or a phonograph record. The cathedral leaves its locale to be received in the studio of a lover of art; the choral production, performed in an auditorium or in the open air, resounds in the drawing room.” (vi) Benjamin’s essay, originally published in 1935, centers primarily on the relatively new technology of motion pictures and the ways in which art has been used and adapted for political motives, but here he makes an important point that we shouldn’t take for granted: Art has not always been accessible.

A quick Google search of the text in the lower left corner of the UMFA’s image— “Traversee la Mer de Glace”— yielded mostly modern tourist information but, towards the bottom of the page, I noticed a strikingly similar image. It was an almost identical shot, even the same title, from the same time period as our image, for sale for €4 from a German vintage postcard shop.(vii) This small discovery opened a floodgate of questions about the nature of the photograph in the UMFA’s collection: who took the photo? Was it the owner of the album, or was this image one that was widely distributed in the area as souvenirs?

The (possible) answer is that the image in the UMFA’s photobook is the work of William England, principal photographer for the London Stereoscopic Company, one of the first companies to license images for commercial reproduction. In 1863 he left the company to pursue freelance work, capturing scenes across Europe, with his most famous and widely-distributed images being those of the glaciers above Chamonix. The postcard I found on the internet is attributed to England and, while it’s likely a different group of intrepid holiday-goers, the similarities in the composition are too striking to ignore. (viii) This, combined with the mark in the bottom left corner (544A), leads me to believe that the UMFA’s image is one of a series that the photographer took on La Mer de Glace. The subsequent reproductions would have been widely available for visitors to purchase to share with friends and family back home.

And that is just what the mysterious owner of our album did. Or, maybe not so mysterious: with some confidence, we can surmise that the owner of our photo album may have been “the artist” Charles Henry Turner.

Turner was an American painter who studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and was later a member of the “White Mountain School” of painting. In the 1880s, he spent some time traveling in Europe. This is backed up by the contents of the Charles Henry Turner Papers in the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian. The Papers include not only letters, catalogues of his paintings, and sketchbooks, but also photographs. Photos of Turner and his wife, his paintings, his New Hampshire studio, and shots of Europe. (ix)

The how and why of the UMFA's ownership of the album are vague now, but the beautiful images remain. Extant prints of some of these views of Europe are few and far between, the negatives long-since lost, but they provide a glimpse into the early days of photography and its burgeoning popularity. On starting this project, I didn’t expect to find so many answers, nor did I anticipate the journey this image would take me on. There is so much of the story I had to leave out.

The work of William England and his colleagues in the 1880s was considered mass market fare in their own time, but the artistry in their work is undeniable today. They tell the story of explorers and innovators, documenting the new, industrializing world. Their work and its popularity was largely responsible for the rapid technological advancements in photography throughout the 19th century and into the 20th, the rise of the film roll leaving the glass plate negative in its wake.

References:

- (i) Robert Hirsch, Seizing the Light: A Social & Aesthetic History of Photography (New York, NY: Routledge, 3rd ed., 2017) 173- 174.

- (ii) Graham Robb, The discovery of France : a historical geography from the Revolution to the First World War. (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1st American ed., 2007) 278-280.

- (iii) Geoffrey Chaucer, John H. Fisher, and Mark Allen, The Complete Canterbury Tales of Geoffrey Chaucer (Boston, MA: Thomson Higher Education, 2006), 9.

- (iv) Geoffrey Chaucer, John H. Fisher, and Mark Allen, The Complete Canterbury Tales, 223-225.

- (v) Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “souvenir (n.),” July 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/1148378054.

- (vi) Walter Benjamin, Hannah Arendt, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology, November 10, 2024, https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/benjamin.pdf

- (vii) I am no longer able to locate this listing. I assume that it sold. I was, however, able to find our exact image from a French seller for €99 as of the date of this writing.

- (viii) Matthew Butson, “William England (1816-1896),” The Classic: a free magazine about classic photography, March 19, 2023, https://theclassicphotomag.com/william-england-1816-1896/.

- (ix) Stephanie Ashley, “A Finding Aid to the Charles Henry Turner Papers, 1875-circa 1973, bulk circa 1890-circa 1910, in the Archives of American Art,” The Smithsonian Archives of American Art, November 16, 2018, https://sirismm.si.edu/EADpdfs/AAA.turnchar.pdf.