By Adelaide Ryder, head photographer and digital assets manager at the UMFA

The Birth of the Photo-Secession Movement

This fall the Utah Museum of Fine Arts will exhibit Photo-Secession: Painterly Masterworks of Turn-of-the-Century Photography. This exhibition of art photography from the early 20th century will be on view from August 24 to December 29, 2024. Who were the Photo-Secessionists and why was their work so pivotal to the advancement of photography as an art form?

In the mid-19th century photography was regarded as a complex technical field that only a trained professional could do. By the 1880s, however, the hand-held camera had become affordable and easy to use, and the “snapshot” became commonplace. Smaller, easier-to-use cameras and the ability to send the film off to a lab for development gave the public accessibility to the medium in a new way. This technological advancement greatly affected the professional photography business, as people began to question the skills needed to make a photograph when "anyone could push a button."

How did photographers respond to this shift in aesthetics and business? Many searched for ways to use photography to express abstract ideas or subjective points of view, shifting from using photography to document objective likeness to illustrating subjective conditions or the subject's inner state. This helped elevate the photographer's status, as the expressive ability of the person behind the camera became as important as the subject. Photographers embraced symbolism and started printing with complex techniques like gum bichromate to elevate their craft above the basic snapshot. Two significant movements were born from this struggle to gain recognition as a legitimate form of artistic expression rather than simply a means of mechanical documentation: Pictorialism and the Photo-Secession.

The camera was seen as a tool, and many felt that photographs visually lacked the "artist's hand," an essential factor in calling something "art." The Photo-Secession movement, founded by Alfred Stieglitz in 1902, aimed to change this perception. Stieglitz and his contemporaries believed photography deserved the same artistic consideration as painting and sculpture. They aimed to elevate photography to fine art, emphasizing the photographer's vision and creativity over mere technical skill. Stieglitz said the Photo-Secession was founded "loosely to hold together those Americans devoted to pictorial photography in their endeavor to compel its recognition, not as a handmaiden of art, but as a distinctive medium of individual expression." (Camera Work, no. 6, April 1904.)

The Photo-Secession movement emerged from the broader Pictorialist movement, which dominated photographic art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While both movements sought to establish photography as an art form, the Photo-Secessionists emerged with their own philosophy.

Similarities

-

Artistic Expression: The Photo-Secession and Pictorialism emphasized the photographer's role as an artist rather than a mere technician. They believed that photography should convey the photographer's vision and emotional intent.

-

Aesthetic Quality: Both movements valued the aesthetic quality of photographs. They often employed techniques like soft focus, manipulation of light, and careful composition to create visually striking images.

-

Influence of Painting: Both were heavily influenced by the aesthetics of painting, particularly Impressionism and Symbolism. They sought to create images that were painterly in style, blurring the lines between photography and traditional fine arts.

Differences

-

Philosophical Focus: Pictorialism focused on creating images that looked like paintings, often using elaborate darkroom techniques to achieve a painterly effect. Photo-Secession, while also influenced by painting, emphasized the photographer's personal expression and the inherent qualities of the photographic medium, sometimes even embracing the "snapshot" aesthetic if it helped to illustrate more hidden ideas and thoughts.

-

Technical Innovation: The Photo-Secessionists were more open to embracing the amateur artist and experimentation in techniques and technologies, whereas the Pictorialists held on to the traditional hierarchy of the European artistic schools of the time. Photo-Secessionists saw innovation as a means to expand photography's artistic potential.

-

Subject Matter: Pictorialists focused on romanticized and idealized subjects, such as landscapes, portraits, and allegorical scenes. The Photo-Secessionists, on the other hand, explored a wider range of subjects, including urban scenes, modern life, and abstract forms. They embraced art movements like Cubism and Futurism, reflecting a broader and more progressive vision of art.

-

Exhibition and Display: The Photo-Secessionists were disenchanted with the outdated salons and gate-keeping ways of many photo schools commonly practiced in Europe. They began publications like The American Amateur Photographer, Camera Notes, and Camera Work to help give a platform to young photographers and people practicing these new ways of image making.

Who were the Photo-Secessionists?

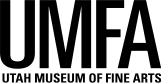

Alfred Stieglitz: The Visionary Leader

Alfred Stieglitz was a driving force behind the Photo-Secession movement. His passion for photography galvanized his dedication to promoting it as an art form. He saw photography as a means of personal expression. He helped catapult the idea that image-making can happen in the darkroom, during the printing process, as much as in the camera.

Stieglitz's photograph The Steerage (1907) is one of the most iconic images in the history of photography. This powerful image captures the crowded lower deck of a transatlantic steamer, where people traveled in steerage class, the part of the ship with accommodations for those with the cheapest tickets. The Steerage is celebrated for its striking composition, which combines geometric shapes and human forms to create a dynamic and balanced visual narrative. Stieglitz considered this photograph one of his most outstanding achievements, as it encapsulated his transition to straight photography, which embraced photographs looking like photographs rather than the painterly qualities of pictorialism. This photograph shows his ability to convey the complexity and depth of human experience through a single image. The photograph is a masterpiece of visual artistry and a compelling social document, reflecting the conditions and aspirations of early 20th century immigrants.

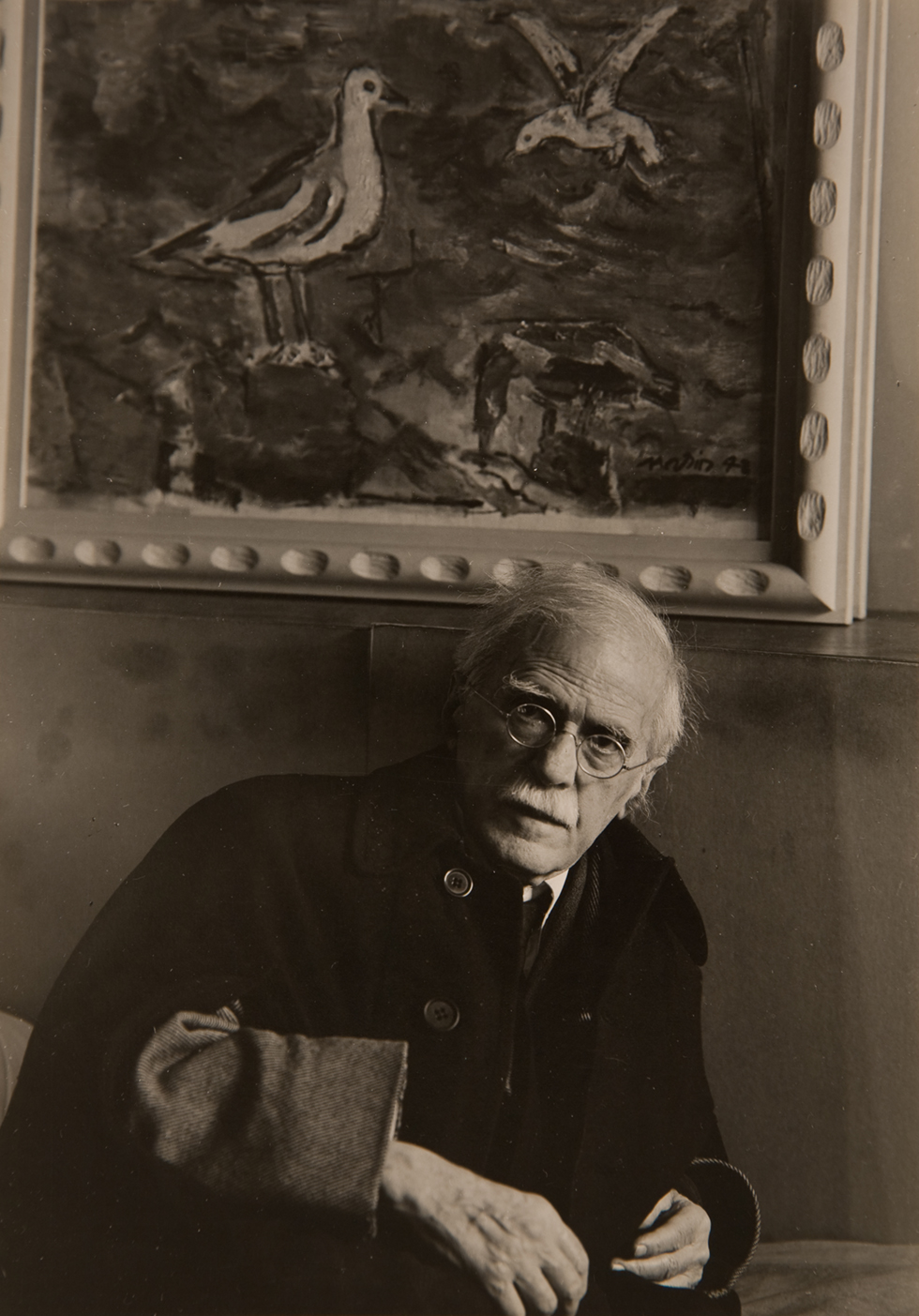

Gertrude Käsebier: The Master of Portraiture

Gertrude Käsebier was known for her compelling portraits and allegorical imagery. Käsebier's work transcended traditional portrait photography by infusing her images with a deep sense of intimacy and character. She believed that a photograph should reveal the inner essence of its subject, and her portraits are renowned for capturing the personality and spirit of the people she photographed.

Käsebier's approach to portraiture was both innovative and empathetic. This image from the UMFA's permanent collection is a perfect example of how she photographed women and children, presenting them with dignity and respect at a time when they were not the usual subjects of portraiture. Her work challenged conventional representations and highlighted her subjects' emotional depth and individuality.

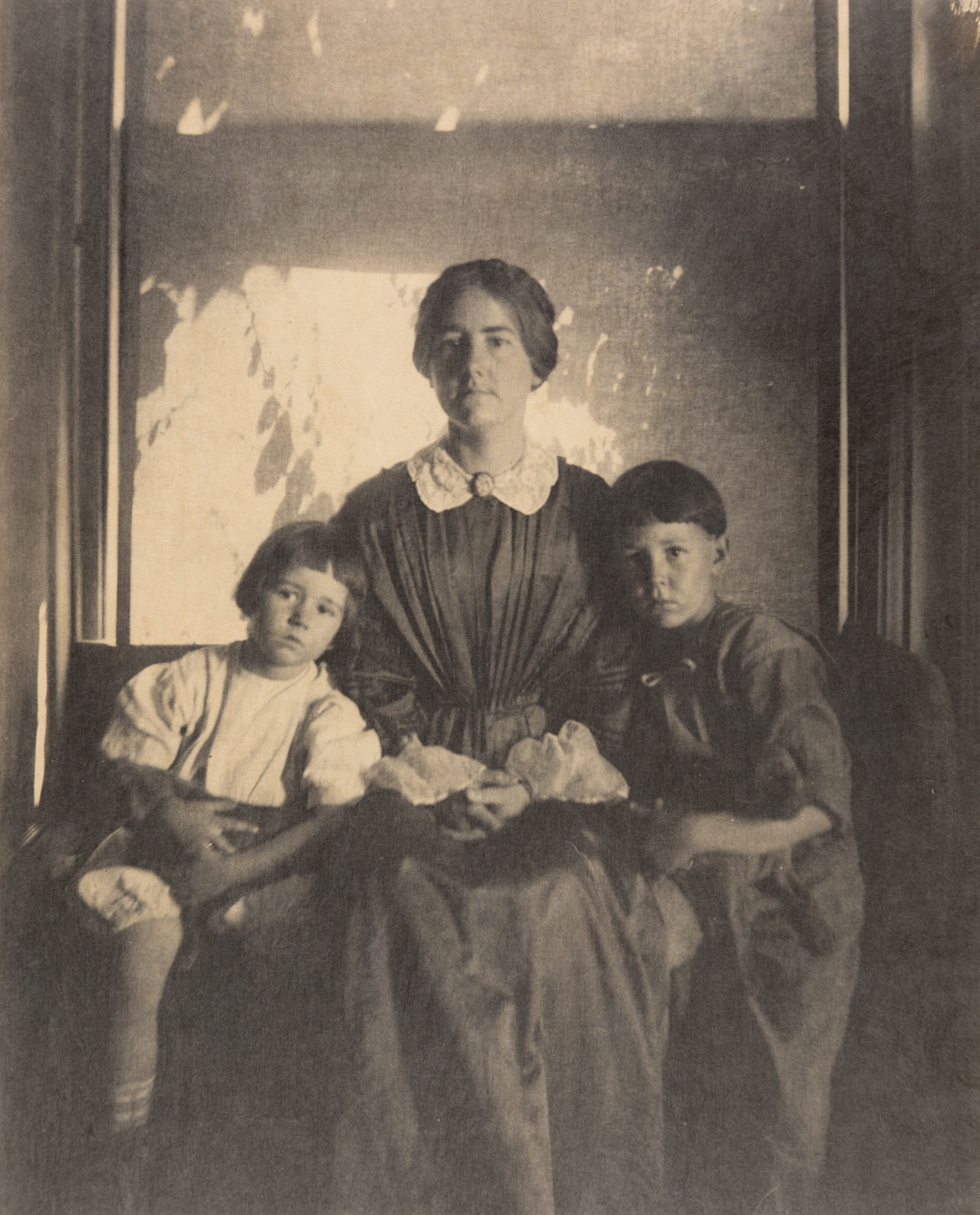

Edward J. Steichen: The Innovator

Edward J. Steichen, a close associate of Stieglitz, brought a unique perspective to the Photo-Secession movement. Steichen was not only a photographer but also a painter, which influenced his photographic style. He experimented with various techniques, including soft focus and manipulation of light, to create both ethereal and visually striking images.

An avid gardener, Steichen propagated and grew a bountiful garden at his French country house. This image of a calla lily is rendered with exquisite detail and tonal richness. Steichen's botanical images showcase his ability to find harmony between nature and art. His meticulous composition and sensitivity to light transform a simple flower into a work of art, reflecting his painterly approach to photography. His botanical works contributed to the Photo-Secession movement by highlighting the artistic potential of natural forms.

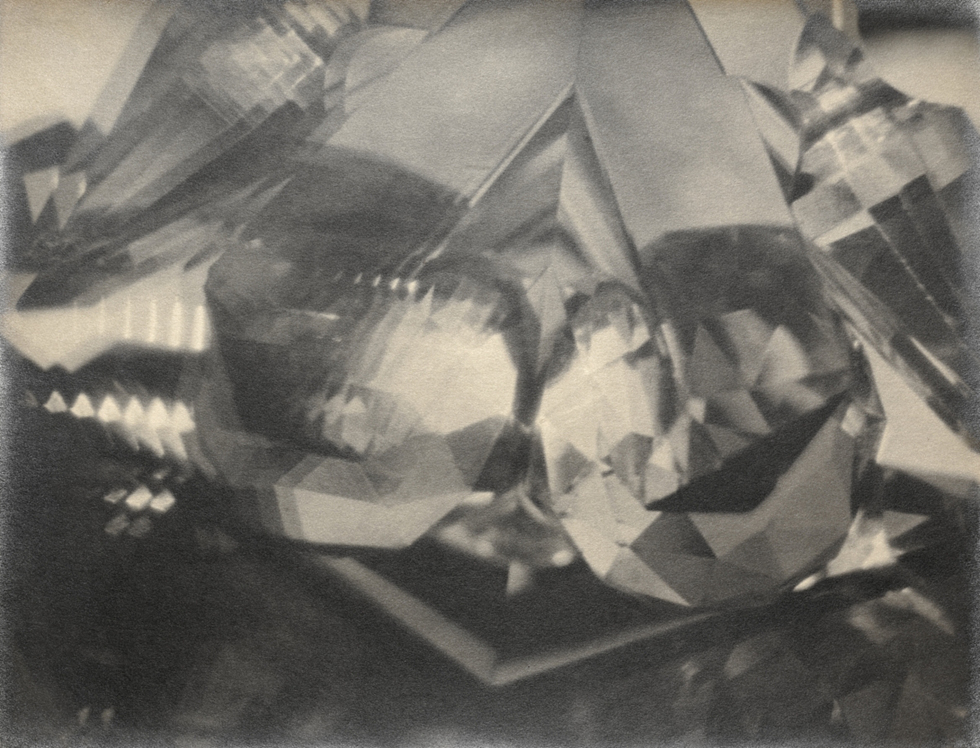

Alvin Langdon Coburn: The Avant-Garde Creator

Alvin Langdon Coburn pushed the boundaries of photography with his innovative Vortographs, created in 1916-1917. These images are considered some of the first abstract photographs, born from Coburn's desire to create art that combined the physical with the spiritual. By placing a vortoscope, a triangular arrangement of mirrors and prisms, over a camera's lens, Coburn created complex images of kaleidoscopic and geometric patterns that simplify the photograph to the essential elements of light and form. This technique broke away from traditional photographic representation, emphasizing form, structure, and abstraction. The Vortographs were influenced by the Vorticist movement, which celebrated dynamic and abstract art. Coburn's pioneering work with these images marked a significant departure from Pictorialism, embracing modernist principles and demonstrating the artistic potential of photography beyond mere depiction. The Vortographs stand as a testament to Coburn's visionary approach and contributions to the evolution of photographic art.

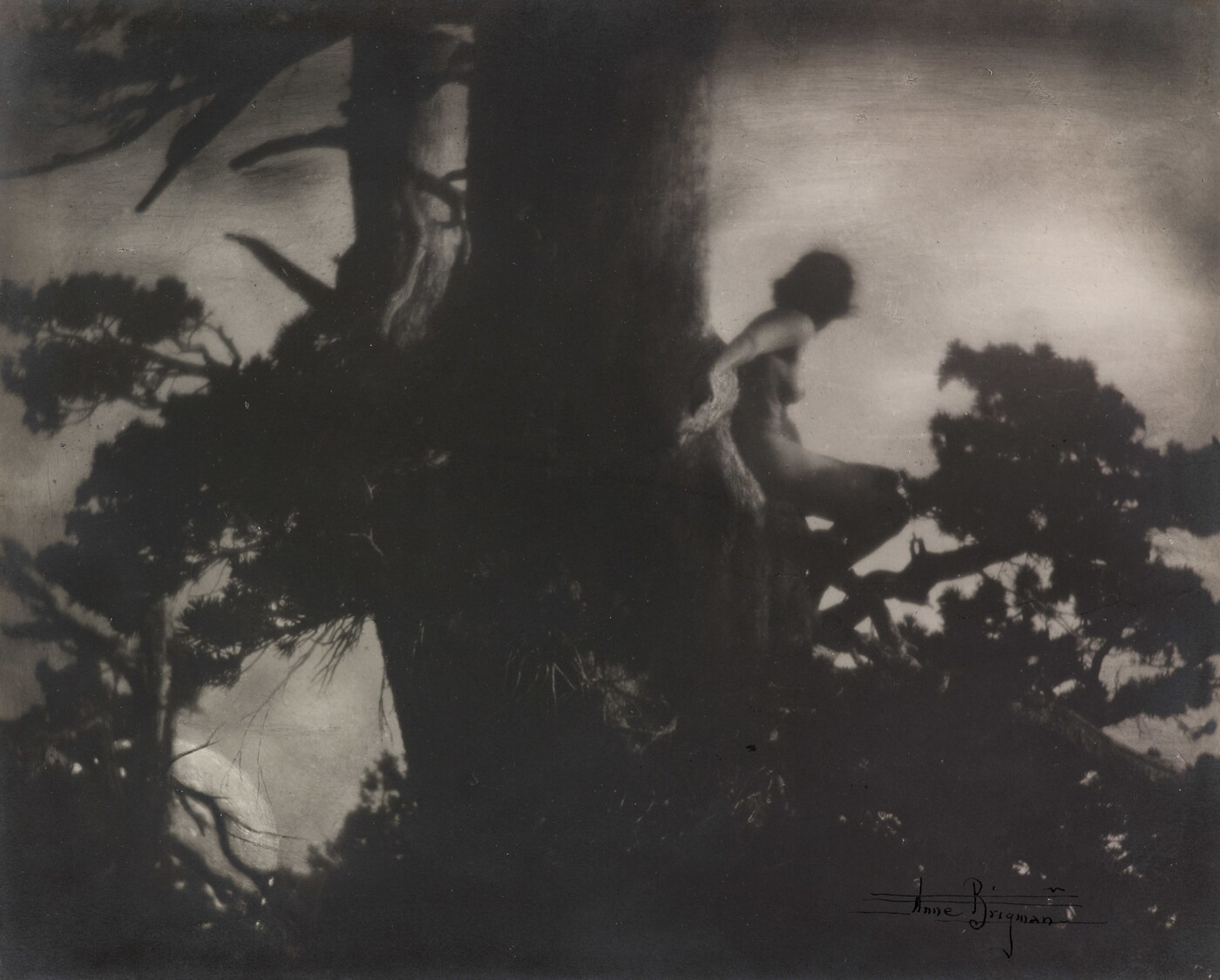

Anne Brigman: The Feminine Mystic of Photo-Secession

Anne Brigman was known for her evocative and mystical imagery. She often placed herself within her compositions, challenging traditional gender roles and expectations. Her connection to the Photo-Secession movement was cemented through her association with Alfred Stieglitz, who published her work in Camera Work and admired her innovative spirit.

Brigman's 1911 photograph The Pine Sprite exemplifies her distinctive style. The image features a nude female figure intertwined with the natural landscape, blending the human form seamlessly with the rugged environment. This work reflects Brigman's themes of femininity, nature, and freedom, aligning with the Photo-Secessionist emphasis on personal expression and artistic experimentation. Brigman's contributions highlighted the movement's inclusive spirit, showcasing how female photographers could assert their voices and artistic visions in a male-dominated field.

Clarence Hudson White: The Romantic

Clarence Hudson White was celebrated for his romanticized and intimate approach to photography. His 1904 image The Kiss perfectly illustrates his unique style. This platinum print on paper captures a tender moment with a soft focus and gentle lighting. The Kiss portrays an intimate scene imbued with a sense of emotional depth. White's use of the platinum printing process, which provides a broad tonal range and exquisite detail, enhances the image's delicate and dreamlike quality. His work reflects the movement's early emphasis on creating photographs that evoke the emotional and aesthetic qualities of fine art while also paving the way for future explorations in photographic expression.

The Role of Camera Work

One of the key platforms for the Photo-Secession movement was the influential journal Camera Work, edited by Stieglitz and Steichen. Published from 1903 to 1917, Camera Work featured the work of Photo-Secessionists alongside essays and critiques that championed the artistic potential of photography. The journal played a crucial role in shaping public and critical perceptions of photography, providing a space for photographers to showcase their work and engage in intellectual discourse.

The Legacy of the Photo-Secession Movement

The Photo-Secession movement had a profound and lasting impact on photography and fine arts. The Photo-Secessionists and their contemporaries paved the way for future artists by advocating for photography as a legitimate art form. Their work demonstrated that photography could be a powerful medium for artistic expression, capable of conveying complex emotions and ideas.

The principles and techniques pioneered by the Photo-Secessionists continue to influence photographers today. Their emphasis on creativity, personal expression, and photography's artistic potential set the stage for the development of modern and contemporary photographic art. Many of the ideas they championed, such as the importance of the artist's vision and the emotional power of an image, remain central to the practice of photography.

Visit the UMFA to see these photographs and other Photo-Secessionist works from August 24 to December 29, 2024, in Photo-Secession: Painterly Masterworks of Turn-of-the-Century Photography.

Author Bio:

Adelaide Ryder is the UMFA’s head photographer and digital assets manager. She teaches the history of photography and darkroom photography at Westminster University.