Renato Olmedo-Gonzalez, manager of annual giving

It isn’t hard for me to pick a favorite from a crowd. Amongst the UMFA’s rich collection of more than 21,000 objects, spanning thousands of years and almost every corner of the world, there is one oil painting that will always stand out to me as worthy of my permanent love and admiration.

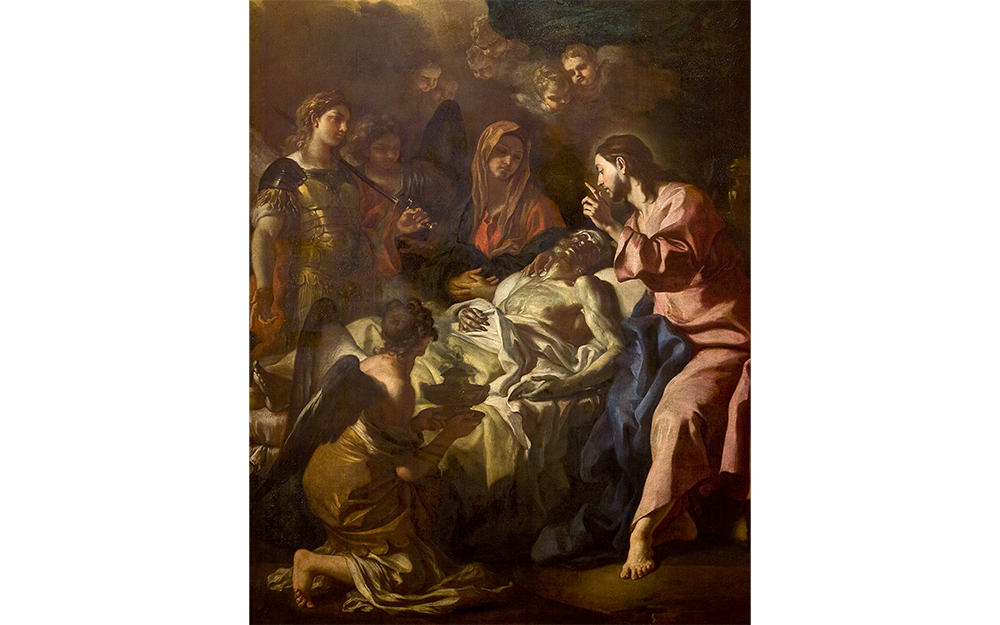

The Death of St. Joseph (ca. 1698–1700) by Baroque Italian painter Francesco Solimena, which currently hangs in our European galleries, holds a very special place in my heart. It was the first piece of art I ever wrote anything about. I initially came across this painting as a senior in high school, during my first ever visit to the Utah Museum of Fine Arts! At the time, I was an AP Art History student and still somewhat new to the United States. What attracted me the most to The Death of St. Joseph—in addition to its dramatic, yet solemn cast of characters, the painting’s rich color palette, and Solimena’s superb use of chiaroscuro—was the story it depicts, one that isn’t found in the Bible, but rather exists in the larger Catholic imagination.

Growing up in Mexico, a deeply Catholic country, and having attended Catholic schools (Marist, to be precise!) all my life, gave me a unique advantage over my high school mates in my appreciation and understanding of art in the Western canon. While my peers were busy learning new art historical terms and complex Catholic symbolism at one fell swoop, my familiarity with Catholic theology allowed me to interpret works of art with much more ease. Unfortunately to me, my life’s deep indoctrination in almost every story of the Bible wasn’t helpful in my initial interpretation of The Death of St. Joseph, as I knew very little about St. Joseph’s life, let alone how he died. Most of the religious stories I knew surrounded Jesus and the Virgin Mary. The Bible is silent about St. Joseph’s life beyond Jesus’ childhood. The painting’s unique subject matter forced me to look a little deeper into what was going on, a process that I now call research. I remembered being enthralled by this painting—it was one of the most enigmatic, confusing, yet emotionally fulfilling things I had ever tried to look at. The more I tried to decipher the painting, the harder it became for me to interpret, let alone write about.

To me, The Death of St. Joseph symbolizes the very first time I looked at art differently—it involved careful looking, some research, and very thoughtful interpretation. In a way, this painting ignited my future: it led me to studying art history in college, and now—full circle!—being a museum professional at the very same institution where I first saw it.

Below is the text I wrote in my response to The Death of St. Joseph in high school, almost 11 years ago, when I saw this painting for the very first time:

“The painting that impressed me the most was The Death of St. Joseph by Francesco Solimena. Its depiction of Saint Joseph is different from anything I’ve ever seen ever before. Saint Joseph is portrayed in his bed literally dying—vulnerable, sick, moribund, and agonizing. He is accompanied in his last moments by his wife, the Virgin Mary, and his adoptive son, Jesus. Catholic theology assumes St. Joseph died before Jesus began his public ministry, and because he was accompanied by both of them at the time of his death, today he is known as the patron saint of a ‘happy death.’

The way how Solimena portrays Saint Joseph’s death contradicts this patronage. To me, this painting depicts a paradox. An anguished Saint Joseph, in his very last moment of life, turns to his son for comfort. Jesus, the only clearly illuminated character in the composition, looks back to Saint Joseph tenderly. He holds his fingers in the blessing position, indicating he has accepted his father’s imminent death. Jesus does this, despite the trauma of this experience, with loving eyes.”

Francesco Solimena, The Death of Saint Joseph, circa 1698-1700, oil on canvas. Purchased with funds from the Marriner S. Eccles Foundation for the Marriner S. Eccles Masterworks Collection, the John Preston Creer and Mary Elizabeth Creer Brockbank Memorial Fund, the Aurelia Bennion Cahoon Acquisition Fund, the Enid Cosgriff Endowment, the Hemingway Family Endowment, and by exchange from Friends of the Art Museum, UMFA1990.048.001.