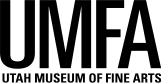

![Francois Boucher, Les amoureux jeunes [The Young Lovers] A painting of a couple in the forest](/sites/default/files/styles/hero_area_2x/public/2023-02/1993.034.008%28DISPOSED%29.jpg?itok=_Nw1zO7D)

Editor’s Note: "At the Heart of It All: Object Origins” is a blog series sharing ongoing research into the origins of artworks in the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA) permanent collection, a dynamic gathering of objects from around the world and across time. Understanding more about what’s in the collection, and being transparent about it, is important as we lean into our goal of decolonizing the UMFA.

A Story of One Artwork Reunited with Its Rightful Owner

By Luke Kelly, UMFA associate curator of collections

A word you may see associated with the museum world, but may not be too familiar with, is provenance. Provenance essentially is the recorded journey of an artwork from its origin through one or more owners to the present day. Art historians and curators use this information to provide more context for a work. An object’s story might include a famous collector or a period when it was part of a larger collection. Provenance research can also help attribute or authenticate a work of art—clarifying or confirming who made it.

More importantly, provenance helps museums ensure that the objects they are collecting meet legal and ethical rules. There are three particularly critical categories of provenance museums must pay attention to: the whereabouts of European artworks collected between 1933 and 1945, when the Nazi regime forced sales and looted thousands of artworks from Jewish collections; archaeological artifacts collected before 1970, when the United Nations passed accords to protect the world’s cultural heritage; and art taken from colonized regions in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when colonial powers looted or illegally removed works from those cultures and locales.

Provenance is an important issue for the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, with our comprehensive collection of more than 20,000 objects from around the globe, most of which were acquired over the past seventy years, through purchases and gifts from donors. Curators have been conducting ongoing research into the collection since the early 2000s and staying up-to-date on best practices around object provenance. But museum-goers may not be aware of this effort because it happens in the background. This and forthcoming posts are meant to bring this important curatorial practice out into the open and share the stories we uncover in the process.

For the first post, we look at Nazi-era provenance research and a discovery about a UMFA painting's previously unknown journey that put the Museum in the international spotlight. This story demonstrates the collaborative nature of provenance research and how the most unlikely of sources helped reunite the work with its rightful owners.

In 2002, Nancy Yeide, then head of the Department of Curatorial Records at the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, DC, took to the Internet while researching her book on the art collection of the notorious Nazi leader (and, later, convicted war criminal) Hermann Goering. She began searching names of artworks that the Nazis confiscated from Jewish families and businesses but that were never returned after the war and were presumed lost. One painting was Les Amoureux Jeunes (The Young Lovers) by Francois Boucher (1707–70.) Search results indicated it was at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts. According to the UMFA’s then-existing records, when the painting entered the Museum's collection as a donation in 1993, it had a brief provenance that took its story back only as far as the gallery where the donor purchased it in 1970. Interestingly, one citation in the gallery’s description of the work was a 1947 French government publication that listed art that the Nazis had looted in France during World War II. The gallery believed the work had been returned to its original owner before the gallery acquired it and later sold it to the donor. Yeide, and later the Art Loss Register, using material from the National Archives, provided crucial information that revealed the true story:

Before World War II, The Young Lovers was in the inventory of Parisian Jewish art dealer Andre Jean Seligmann (1898–1945). The Seligmann family were well-respected dealers with galleries in Paris and New York. In the summer of 1940, as the Nazi army occupied Paris, Seligmann managed to evacuate his family to America. He was not able to move his painting inventory out of the country, however. So he deposited all of his paintings, including the Boucher, into a bank vault in Paris, perhaps receiving assurances they would be safe.

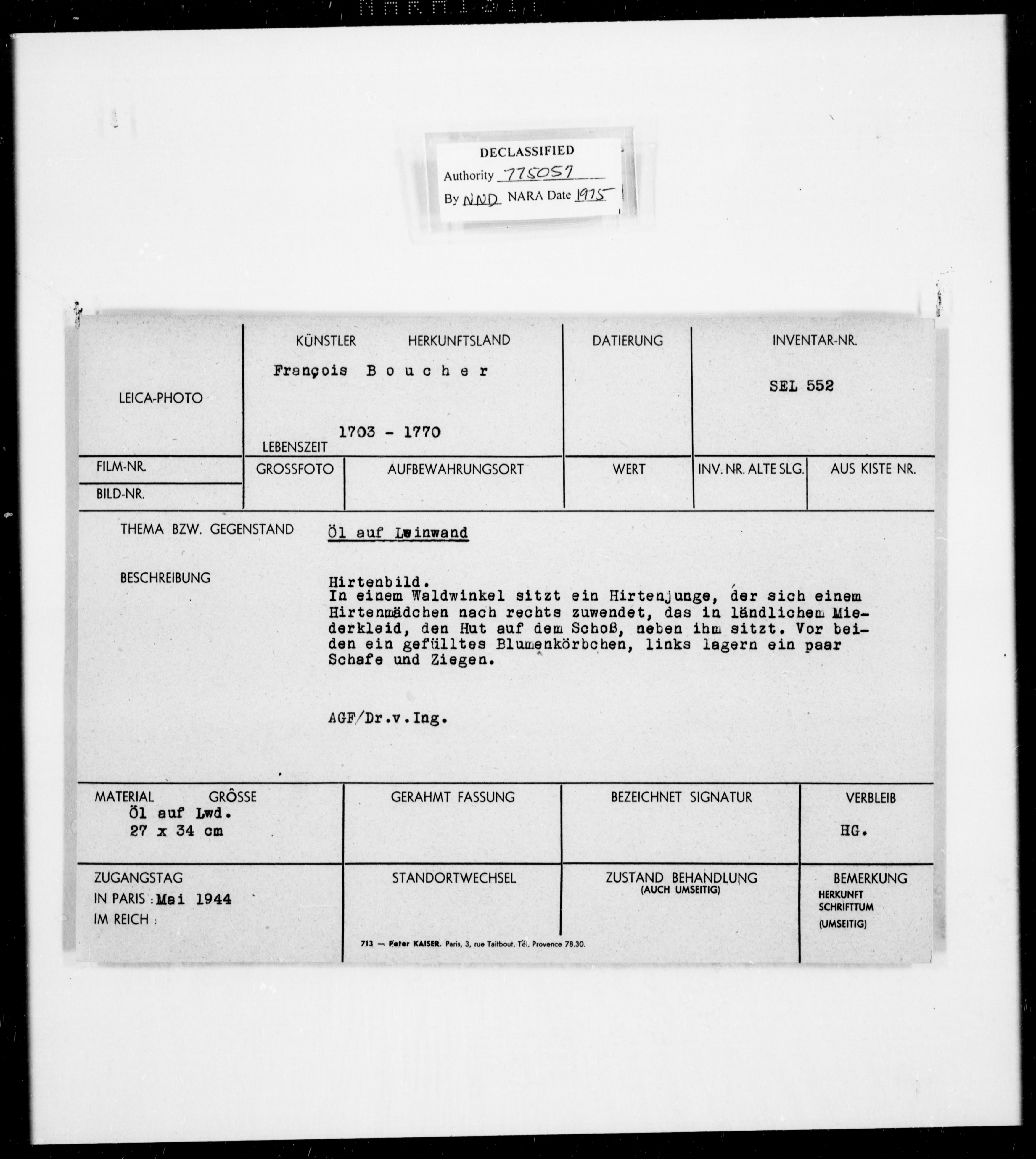

A series of Nazi records then pick up the trail of the painting’s whereabouts and reveal the Nazis’ terrifyingly efficient looting of Jewish property. First, a report filed in September 1941 lists the contents of the bank vault, including the Boucher, belonging to the “Jew Andre Seligmann.” An elite SS looting unit moved it to the Jeu Du Paume art center in Paris, which the Nazis used as storage for numerous stolen artworks. An art historian named Dr. von Ingram then created an inventory card for The Young Lovers with the number “SEL 552.”

The next mention comes in December 1941 in a list of artworks, including the Boucher, moved to the personal collection of Reichsmarshall Hermann Goering. The last update came in early 1945. Now in Germany and cataloged as “no. 489,” the painting was part of a shipment from northern to southern Germany, to keep it out of the allies' hands. At this point, the Boucher seemingly disappeared from history. After the war, a French investigation using the same documents could not locate The Young Lovers and speculated it was destroyed in transit.

This rediscovered journey of the Boucher contradicted the earlier assumption that the painting had been returned to Seligmann after the war. The UMFA, working with the Art Loss Register, contacted the heirs to start restitution of the work. In a 2004 ceremony that attracted worldwide attention, the Museum reunited Seligmann’s descendants with the painting after fifty years. In a 2006 documentary, The Rape of Europa, David Carroll, then UMFA’s director of collections and exhibitions, spoke for UMFA staff and supporters when he said, “It was a little sad when I began to think about returning the painting—it’s been an important part of our permanent exhibits—but I also saw the larger moral responsibility. We can’t make amends for the millions of lives that were taken, but we can do something simple, return something stolen, and confer a little humanity back on all of us.”

When Yeide initially conducted her research on the Boucher, she had spent countless hours going through thousands of paper files at the National Archives. Since then, many records relating to Nazi seizures of art at the Archives have been digitized and are now searchable online. These materials and newer databases are making it easier for UMFA curators to uncover and share future stories about the collection.