A Research Journey to Uncover the Provenance of an Ancient Artwork

By Luke Kelly, UMFA associate curator of collections

This is the second blog in the series on provenance and why it matters for museums. There are three particularly critical categories of provenance museums must pay attention to: the whereabouts of European artworks collected between 1933 and 1945, when the Nazi regime forced sales and looted thousands of artworks from Jewish collections; archaeological artifacts collected after 1970, when the United Nations passed accords to protect the world’s cultural heritage; and art taken from colonized regions in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when colonial powers looted or illegally removed works from those cultures and locales.

In this post, we will explore the provenance of an ancient art object in the UMFA’s permanent collection. Archaeological material and ancient art fall under specific Association of Art Museum Directors guidelines that accredited museums must follow when acquiring objects.

White ground oil flask (lekythos), Greek, Athens, Classic period, 450-420 BCE, Terracotta with glaze, Purchased with funds from the Hayden H. Huston Fund and the John Preston Creer and Mary Elizabeth Brockbank Creer Memorial Fund, UMFA2019.6.1

In 2019, the UMFA acquired an ancient Athenian white-ground lekythos (UMFA2019.6.1) from Kallos Gallery in London. This late 5th century (450-420 BCE) oil jar was originally part of funerary rituals where mourners would bring gifts to honor the dead. This vessel represents the third decorative technique Athenian potters produced alongside black-figure (UMFA1990.001.001) and red-figure ware (UMFA2000.8.1). A painter created the white ground by covering the ceramic vessel’s surface with a lead-based white pigment. They would then paint an image onto the surface using various colors, resulting in more realistic imagery than the black and red figure techniques. The technique’s downside was the white lead pigment easily flaked off, making good examples like this vessel rare today. However, provenance is a far more important determining factor when acquiring an ancient art object than condition.

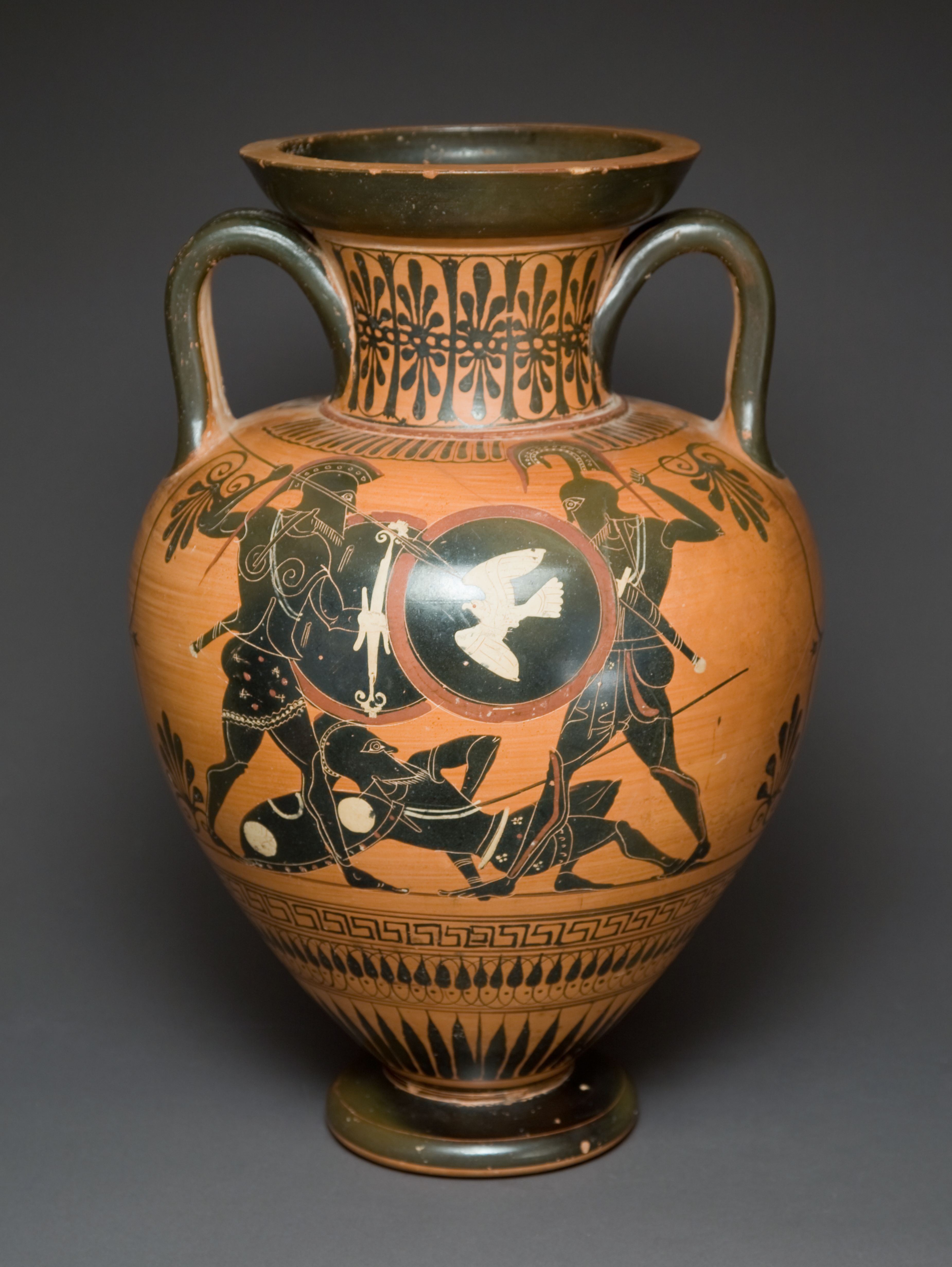

Black Figure Ware Two Handled Jar (Amphora), Manner of Antimenes Painter, Greek, Attica, Late Archaic Period ca. 510-500 BCE, Terracotta with glaze, 17 x 12 x 12 in., Purchased with funds from Friends of the Art Museum and Emma Eccles Jones, UMFA1990.001.001

Red-Figure Ware Wine Cup (Kylix), Related to the style of the Thalia Painter, Greek, Athens, found in Italy, ca. 510-500 BCE, Terracotta with glaze, 5.25 x 16.625 x 13.25 in., Purchased with funds from the Marriner S. Eccles Foundation for the Marriner S. Eccles Collection of Masterworks, UMFA2000.8.1

The American Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) has strict guidelines for museums acquiring archaeological material and ancient art. These recommendations stress rigorous research and consider only objects that can be traced outside their country of origin on or before November 14, 1970, the date the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) passed the “Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.” The AAMD guidelines are a stronger threshold than current US law and bilateral agreements with other countries.

How do museums ensure a potential acquisition or donation’s history meets these guidelines? In the best cases, ancient art objects come with documentation provided when an object enters a gallery or personal collection as well as previous owners’ records. These sources could be as simple as a sales receipt or referenced in correspondence and photographs. Museums then use this material to verify the object’s history. The more documentation an object has, the stronger the case to support the collecting history. For the UMFA’s lekythos, the Museum’s sources produce a provenance dating back to 1921.

The object itself provided the first provenance source. It first appeared in the collection of George Edward Spencer Churchill (1876-1964). Churchill, whose cousin was the famous Prime Minister Winston Churchill, acquired numerous examples of ancient Chinese, Persian, and Greek pottery in his lifetime. While no record exists of how he purchased the vessel, a clue to when he acquired it comes from its foot. Early collectors would annotate pieces with bits of data relevant to them. Here, he added in ink the year “1921.” A second number “60,” is most likely an inventory number.

White ground oil flask (lekythos), Greek, Athens, Classic period, 450-420 BCE, Terracotta with glaze, Purchased with funds from the Hayden H. Huston Fund and the John Preston Creer and Mary Elizabeth Brockbank Creer Memorial Fund, UMFA2019.6.1

Scholarly essays and books are important resources providing outside verification of an object’s story. Sir J.D. Beazley listed the lekythos in his 1963 Attic Red-Figure Vase Painters 2nd edition. Beazley was a classical archaeologist and an early authority on Greek vases. He confirmed George Spencer Churchill as the owner of the lekythos and added new information by identifying the vase based on the decoration as “associated with the Quadrate painter.” This name was an invention of the author as ancient sources made little mention of Athenian potters and vase painters.

Auction records add to an object’s history by tracking changes of ownership. This lekythos has gone to auction twice. It appeared as lot number 337 in a 1965 Christie's London auction following Churchill’s death earlier that year. The catalog includes the earliest known image of the work. Arthur and Marjorie Silver of Los Angeles, California purchased the object and held it in their collection until 1991.

William Suddaby of Florida then acquired it from a Sotheby's New York City auction that same year. He sold it in the 2010s to a gallery that later sold it to Kallos Gallery of London where the UMFA’s would then acquire it for its collection.

Together these sources establish that the lekythos’ provenance meets the AAMD guidelines. Research is still ongoing to learn how Churchill bought the piece. As a part of the UMFA’s on-going efforts to be transparent about collection practices a QR code linking to the object’s provenance will join the object on display. See it in the Ancient Mediterranean Art gallery now. In addition, the Museum shared the collecting history information with the Beazley Archive Pottery Database, an online resource for ancient Athenian pottery which you can view here.