Annie Burbidge Ream, Assistant Director of Learning and Engagement

Utah Museum of Fine Arts, University of Utah

“This is sort of the door. At first you notice right at the back that it’s green, right? There’s not really much you can say about it, I mean it’s just a green door. We’ve all seen green doors at one time in our lives. It gives out a sense of universality that way, a sense of kind of global cohesion. The door probably opens to nowhere and closes on nowhere so that we leave the Hotel Palenque with this closed door and return to the University of Utah.”

-- Robert Smithson, Hotel Palenque, January 24, 1972

Fine Arts Auditorium, University of Utah

Robert Smithson is best known for Spiral Jetty, his 1,500-foot-long, 15-foot-wide earthwork of basalt rocks that extends out into Utah’s Great Salt Lake at Rozel Point. However, the large earthwork is not the only evidence of Smithson in Utah. The Utah Museum of Fine Arts’ permanent collection has several works of art by Smithson including photographs, paintings, collages, drawings and an original 1970 copy of the film Spiral Jetty that was recently rediscovered in the archives of the University of Utah’s Marriott Library. Lesser-known is that in 1972 Robert Smithson was appointed visiting professor in the Department of Architecture at the University of Utah.

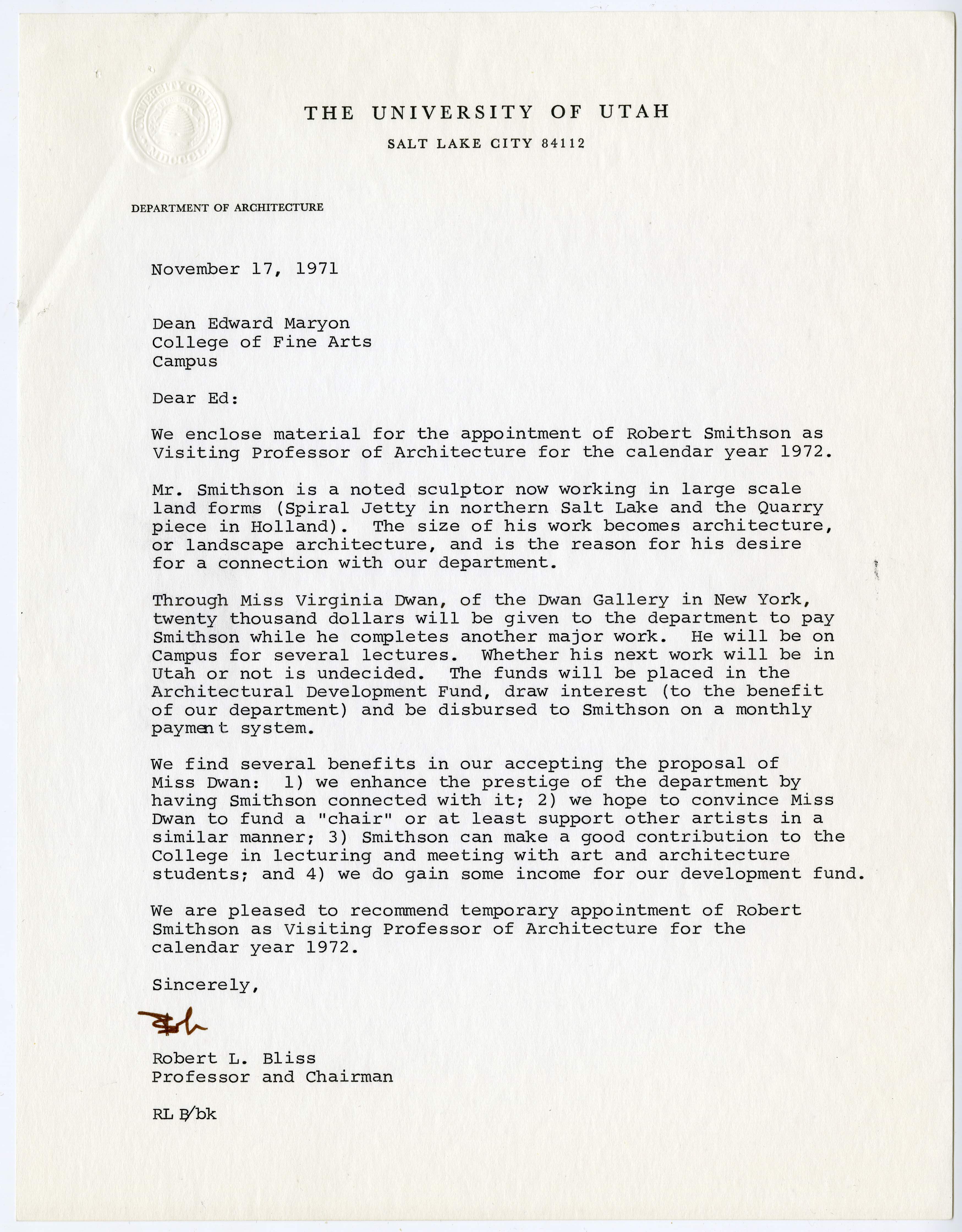

In 1970, the chair of the University of Utah’s Department of Architecture Robert Bliss (1921–2018) and artist and architect Anna Campbell Bliss (1925 – 2015) were among some of the first to see Spiral Jetty. Bliss and Smithson had a mutual friend, Jan van der Marck, then curator of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, who brought the Blisses to Spiral Jetty and eventually Smithson to the University of Utah. A year later, in the fall of 1971, Bliss was introduced to Virginia Dwan, Smithson’s gallery representation, at a social function at Spiral Jetty. Dwan approached him about the possibility of Smithson spending some time at the University of Utah in a teaching capacity. By November of 1971 much of the paperwork was already in progress to appoint Smithson as a visiting professor. Initial conversations between Bliss and Dwan detail how Smithson would be on campus for several lectures and to teach some graduate level workshops, as well as to plan a major work. In his initial letter proposing the appointment to Edward Maryon, the Dean of the College of Fine Arts, Bliss lists four important benefits in accepting Virginia Dwan’s proposal to appoint Smithson to the position (fig. 1):

“1) we enhance the prestige of the department by having Smithson connected with it; 2) we hope to convince Miss Dwan to fund a “chair” or at least support other artists in a similar manner; 3) Smithson can make a good contribution to the College in lecturing and meeting with art and architecture students; and 4) we do gain some income for our development fund.”

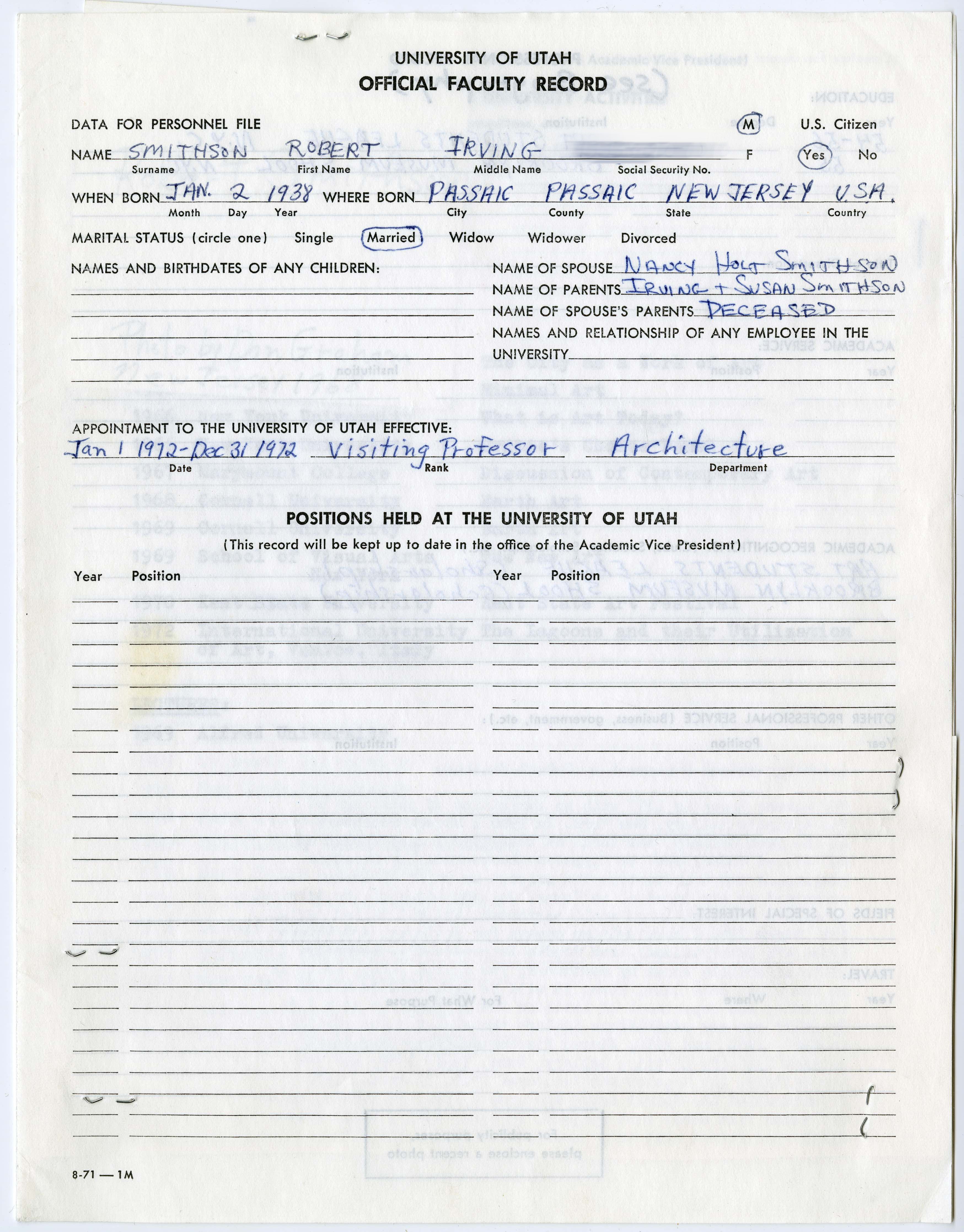

On December 14, 1971 Robert Smithson was officially approved and appointed to the position of Visiting Professor of Architecture for the calendar year of 1972 (fig. 2 and 3). Inspite of the excitement and sense of possibility evident from the long trail of paperwork connected to Smithson’s appointment, his presence on campus was fleeting, comprising of only two events, a lecture titled Hotel Palenque and a screening of his film, Spiral Jetty.

On January 24th, 1972, standing on the stage of the Fine Arts Auditorium at the University of Utah, Smithson presented Hotel Palenque to an audience of approximately 250 students, faculty, and community members. In his talk, Smithson showed slides of an old, crumbling roadside hotel in the Chiapas region of Mexico, which he had visited with his wife, artist Nancy Holt, and gallery owner, Virginia Dwan in 1969. In a 42-minute slide presentation, Smithson who, according to Robert Bliss, was accompanied by a glass of Scotch, narrated 31 photographs he’d taken of the hotel in the manner of a family vacation slideshow, flipping from one slide to another, analyzing the buildings and the grounds in a deadpan manner.

“Here we have some bricks piled up with sticks sort of horizontally resting on these bricks. And they signify something, I never figured it out while I was there but it seemed to suggest some kind of impermanence. Something was about to take place. We were just kind of grabbed by it.”

His meandering observations snake around the periphery and range from the illuminating, to the humorous, to the boring, simultaneously straddling understanding and complete nonsense. “You should be getting the point that I am trying to make, which is no point actually,” comments Smithson. Yet, Hotel Palenque is consistent with the artist’s interest in entropy, human vs. geological timescales, and human impact on the landscape in that it elevates the mundane spaces of the decaying hotel as places of importance, focusing special attention to details of cast-off bricks, un-built walls and empty swimming pools. Rarely has so much thought been put into a run-down building! Morevover, Smithson pointedly disregards Palenque’s famous Mayan ruins, mentioning them only once: “If you could see actually back there you might remotely be able to pick up a fragment of the Palenque ruins, the temples.. the things we actually went there to see, but you won’t see any of those temples in this lecture.” Disrupting the audience’s expectations, this chaotic yet acute study of a dilapidated building must have been quite an interesting encounter for the students and professors of architecture.

In his lecture, Smithson reminds us how careful and creative consideration of peripheral places can illuminate our time and how ultimately they can be the most telling documents of who we are. Smithson’s tour through Hotel Palenque is not a discovery of great conclusions, but rather it highlights the enjoyment in discovering the overlooked. More than a site and historical record, the Hotel Palenque lecture has morphed from a strange happening to a work of art now part of the permanent collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Unknown at the time, this lecture is now the primary trace of Smithson’s little-known appointment at the University of Utah.

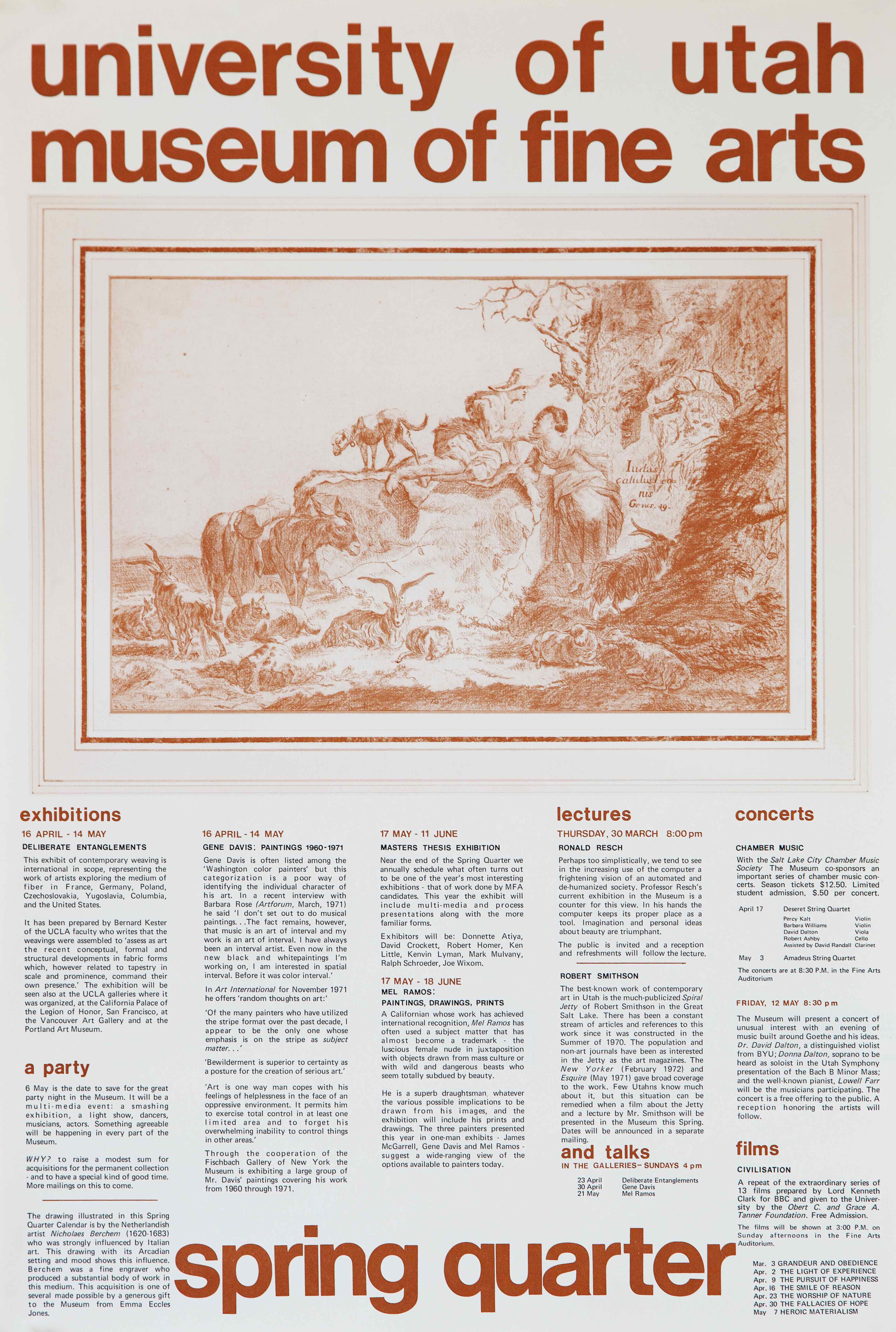

Information about Smithson’s second engagement on campus is well documented on paper, but absent in collective memory. Archival records for his screening of the film Spiral Jetty (1970) include scribbled notes “leave for Utah” and “movie 3:00” in Smithson’s personal calendar on May 13 and 14, 1972; as well as two small advertisements: a poster calendar and a postcard marketing the event. However, it remains a mystery if the film screening actually happened. Robert Bliss had no recollection of the event, and there doesn’t seem to be anyone who remembers attending. (*If someone reading this knows anything, please contact me!)

According to the calendar highlighting events for the museum (at the time named The University of Utah Museum of Fine Arts, today the Utah Museum of Fine Arts), “Few Utahns know much about it [Spiral Jetty], but this situation can be remedied when a film about the Jetty and a lecture by Mr. Smithson will be presented in the Museum this spring. Dates will be announced in a separate mailing” (fig. 4). The separate mailing is a blue and white striped postcard that details “A showing of Mr. Smithson’s film about Utah’s famous Spiral Jetty. Comments by Mr. Smithson on Sunday afternoon, 3:00 PM, May 14, 1972. Museum Auditorium” (fig. 5). These two marketing pieces seem so appropriate in their not-so-telling record of an event that maybe occurred and maybe didn’t, an anti-climactic end to Robert Smithson’s time at the University of Utah.

Smithson’s appointment at the University of Utah concluded with many of its initial expectations unrealized. The Hotel Palenque lecture and a scheduled film screening came in place of an appointment that was initially anticipated to involve multiple lectures, the planning of a new work, and teaching. The lack of collective memory about the Spiral Jetty film screening and “comments by Mr. Smithson” leaves one tantalized with the possibilities of the unknown. With so much documentation of Smithson through his prolific writing, sketches and film documentation, missing even the smallest record of the May 14, 1972 film screening leaves a heavy absence. Was the film shown, was Smithson there, how many people attended, and what were their reactions to the film? What new understandings into the cut-short world of Smithson could have been revealed? Why did an appointment that held so much promise evaporate into such a small contribution? While the traces of Smithson at the University of Utah are indeed ghostly, there is something keenly intriguing about his persistent absence. His appointment, in the end, remains largely a phantom, resulting in few events and leaving even fewer traces. Yet, even if one could see through the murky haze of history, it is uncertain that anything would be there. Smithson was elsewhere.

*This essay is an excerpt from my Master of Arts thesis of the same name through the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Utah detailing my original research of Robert Smithson at the University of Utah including an oral interview with Robert Bliss, in which some of his comments were summarized here.

On the occasion of Spiral Jetty's fiftieth year, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts invited four brilliant Utahns to share their perspectives.

Serving as Assistant Director of Learning and Education and Curator of Education at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, Annie Burbidge Ream oversees the administration of K-12 School and Teacher Programs, including planning, statistics, and reporting; curricular development; and manages the Education Collection. In addition, Annie utilizes UMFA objects and resources to create hands-on, question-based experiences for teachers and students across the state of Utah, as well as docent trainings emphasizing the importance of experiential learning. Annie approaches her work with the philosophy that art is for everyone and with goals to assist in the development of visual literacy and cultivate critical thinking, creativity, and curiosity. Annie has a deep love for American Art after 1960, especially Land art, and can be found exploring sites across the West. Annie received the 2016 Utah Museum Educator of the Year by the Utah Art Education Association as well as the 2016 Pacific Region Museum Education Art Educator Award from the National Art Education Association.