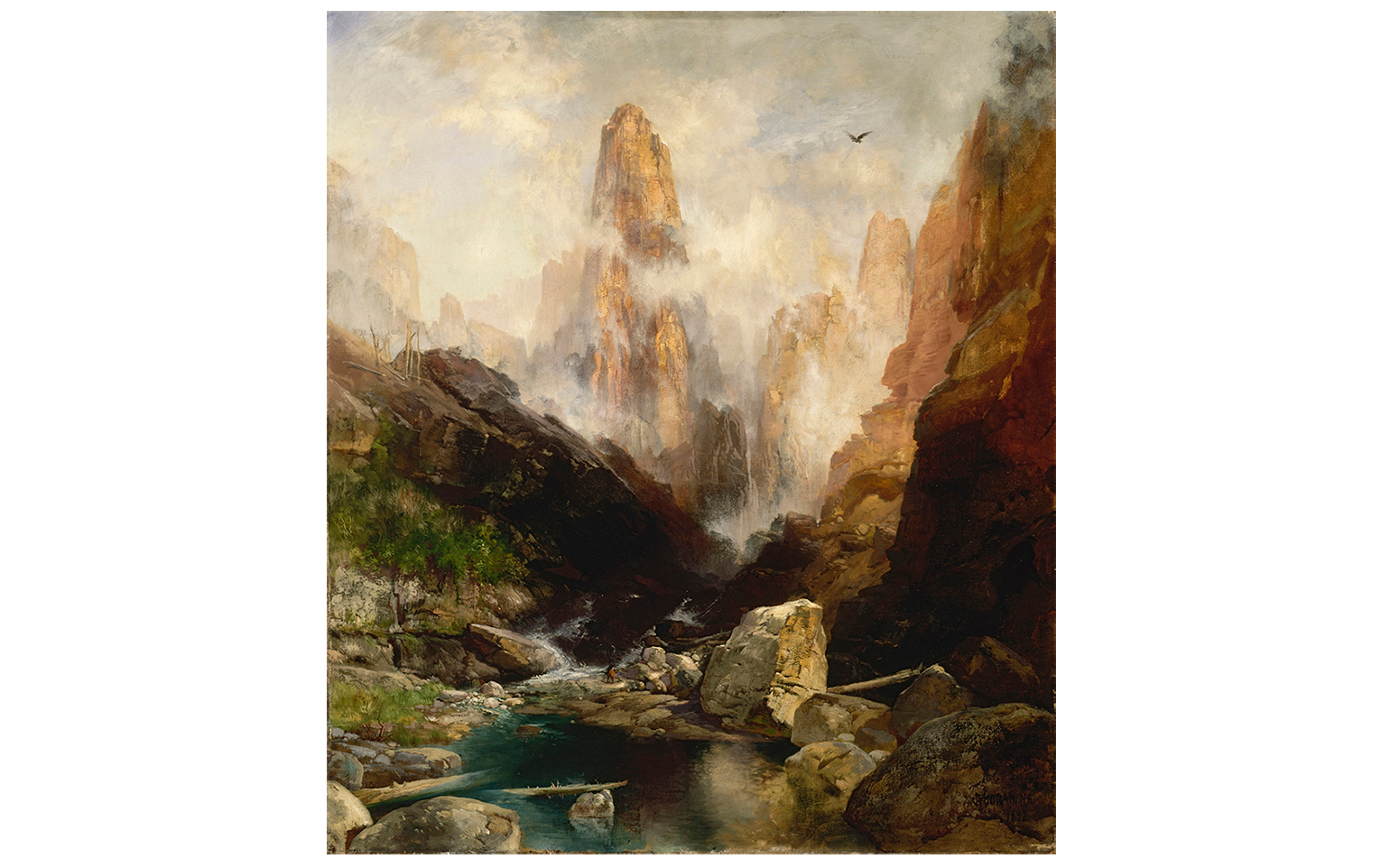

Facing Thomas Moran’s staggering depiction of Utah’s well-loved desert south can leave observers disoriented, especially those of us who consider ourselves acquainted with the red rock landscapes of Kanab. Mist in Kanab Canyon, Utah (1892) is a strangely daunting representation of the region, made mystical and somewhat unfamiliar by the artist’s use of idealized naturalism to portray the scenes he saw (or came close to seeing) during his expedition almost twenty years prior. The group, including photographer John K. Hillers and journalist Justin Colburn, led by John Wesley Powell, embarked on this expedition towards the beginning of photography, prompting painters like Moran to find balance between the new level of realism made available through photographs and their own imaginative visions of the breathtaking, complex landscapes before them. Colburn’s writings from the expedition in Picturesque America disclose that the group never actually made it to the vantage point in the painting during Moran’s portion of the trip, leaving him to create the scene entirely from his memory and photographs that he received from Hillers after his return.

The landscape painting is unique in its vertical orientation, which corresponds with the towering rock structures jetting upwards from the canyon, exaggerated in their height-to-width ratios. The path ahead seems to be obstructed by massive walls of limestone and dense fog wafting into the canyon, perhaps representing the actual roadblocks that Moran encountered on his journey, forcing the expedition to take another route to the Grand Canyon. Moran creates a beautiful rendition using colorful earth tones and immense scale to portray ground unbroken in a "eureka" moment only explorers truly understand. However, as Stephanie Stebich, director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, pointed out during her October visit to Salt Lake City, the image he creates is not one of total seclusion; “there is a figure—likely of a Native American”—depicted in the painting towards the bottom center.

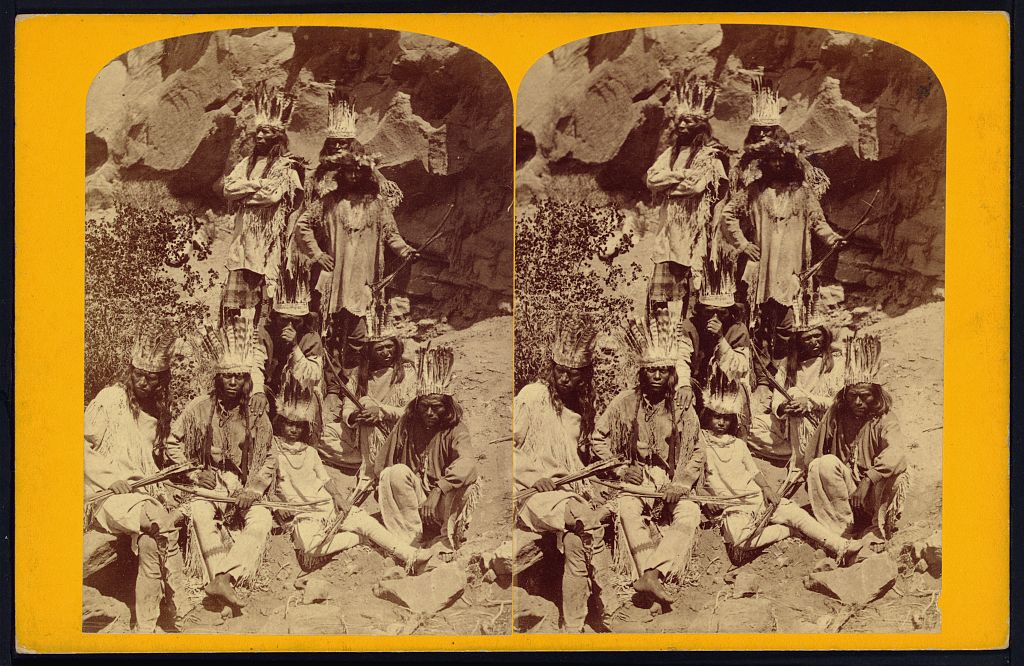

This figure’s inclusion in the painting introduces the scene as one of historical significance beyond the goals of the expedition. During the decade prior to Moran’s 1873 journey through the American southwest, Kanab’s native population underwent a dramatic uprooting. The region had been occupied predominantly by the Kaibab Paiute tribe until the early 1860s, when Mormon settlers encroached on the area. Within a year, the tribe’s water supply had been compromised by settlers, and within a decade, the tribe had lost eighty-two percent of its population (down to 207 members) primarily due to starvation, according to A Kaibab Paiute Ethnohistorical Case. Despite this decline, the John Wesley Powell expedition interacted with Kaibab Paiute children and even used the help of members as guides while in Kanab. Proving that Moran was not alone in creating idealized images, Hillers photographed a group of men in the tribe “dressed in fake headdresses” to meet the stereotypical expectations of Euro-American travelers. Another photograph of Hillers’s, included in Kevin J. Avery’s Forgotten Landmark of a Lost Friendship, displays a similarly dressed Paiute boy beside Thomas Moran and Justin Colburn in Kanab that same year.

Given the various forms of fantasy at work in the creation of this painting, visitors have expressed many opinions about what is real and what is not. What do you think? Does Moran’s misty scene resemble southern Utah? Who do you think the figure is, if there is one at all? Take a closer look at Mist in Kanab Canyon, Utah (1892) at the UMFA while it is on loan from the Smithsonian American Art Museum through October 4, 2020.

Jacklyn Polaco recently became the communications coordinator on the UMFA's marketing team. She graduated from the David Eccles School of Business at the University of Utah and is passionate about sustainability, music, and the great outdoors.

January 2, 2020.