A Complex of Interlocking Forms: Campus Arts and Culture at the University of Utah

The [Art and Architecture] department’s two buildings are a complex of interlocking forms and spaces that create an intimate and human atmosphere which nurtures creativity.– Art and Architecture Center booklet, University of Utah, 1971.

In a very, very definite way I wanted nothing to do with high school, and I had no intention of going to college.– Robert Smithson, interview with Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, 1972

Spiral Jetty’s fame spread rapidly through the international art world following its April 1970 completion, but for many coastal Artforum readers, the idea of "Utah" rarely went beyond spartan desertscapes with a vaguely "pioneer" past. Yet those living in the state during the seventies knew Salt Lake City as a cosmopolitan metropolis percolating with creative energy.

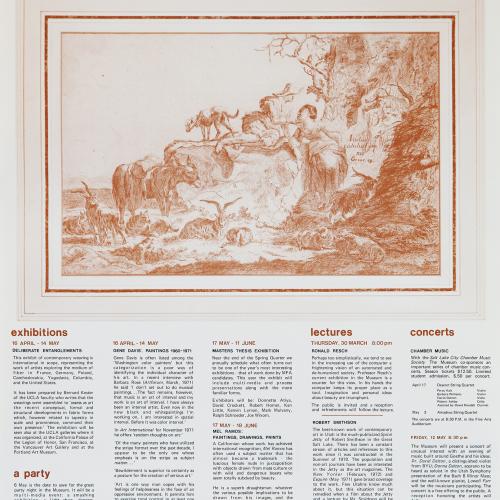

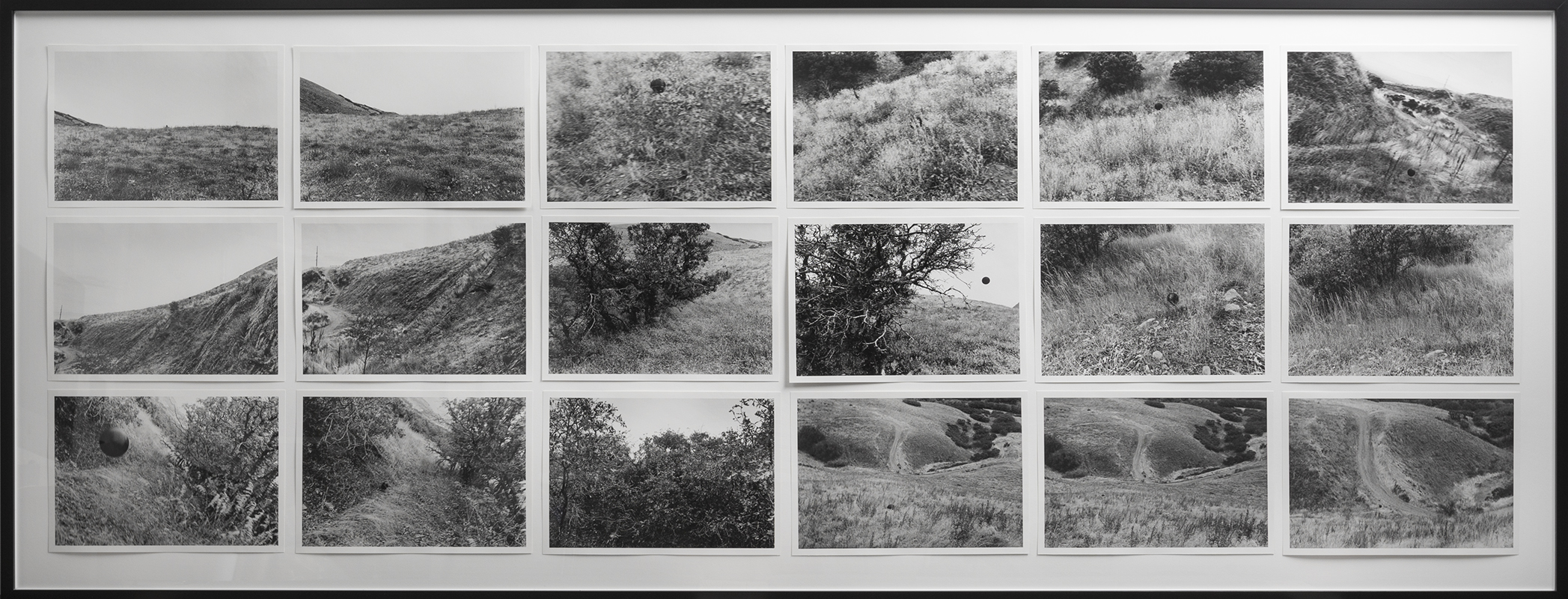

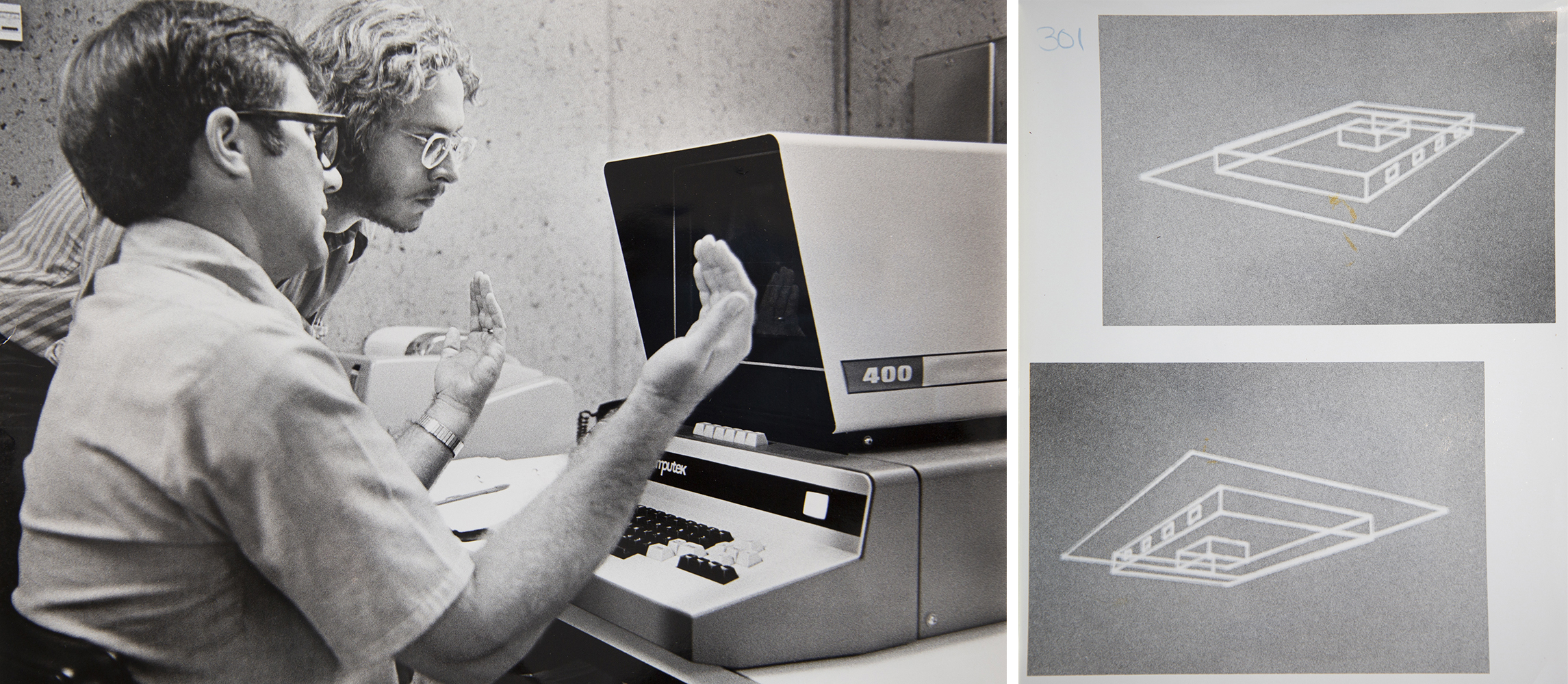

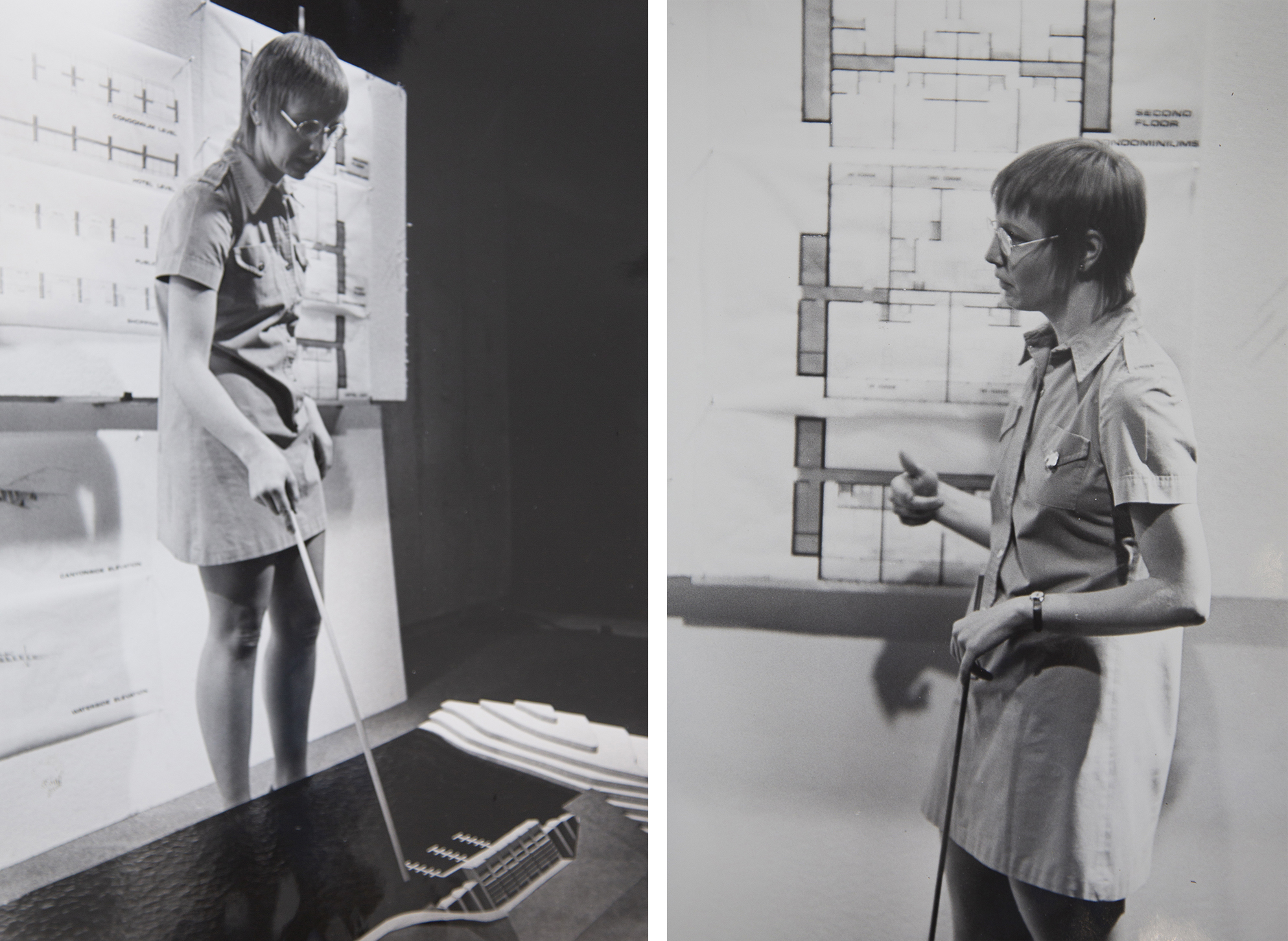

In the fall of 1970 – and 290 days behind schedule – the University of Utah debuted a four million-dollar Art and Architecture Center to meet burgeoning student demand for arts education. Campus arts were interdisciplinary and innovative, as architecture and photography students and faculty collaborated with those in dance, film, and computer science. From the late 1960s, up-and-coming art students such as Paul McCarthy and Richard Taylor, whose work is shown below, were exposed to a rotating roster of internationally-regarded artist faculty at the University of Utah. Among the visiting professors were Alex Katz, James Turrell, Robert Irwin, Dale Eldred, Will Insley, and Robert Smithson.

The elaborately illustrated brochure above introduced readers to the newly completed facilities for the University of Utah’s Departments of Art and Architecture. Fine arts faculty pled for expanded space for their department for many years. In 1970 – the same year that Smithson completed Spiral Jetty – and after many delays, those pleas were finally answered, as the new complex boasted technologically advanced equipment, spaces for photography, film, and computer graphics, as well as traditional techniques and studio spaces. The complex also provided a new space for the Utah Museum of Fine Arts.

While the booklet offers an enticing view of the facilities, other archival documents demonstrate that the project had been riddled from the beginning with difficulties, ranging from glaziers initiating strikes and slow-drying concrete to acoustic problems that made some spaces virtually unusable after they were completed. The memos below are just a few examples from University Facilities records that chronicle difficulties with the new complex; click on them to learn about the collection from University Archives.

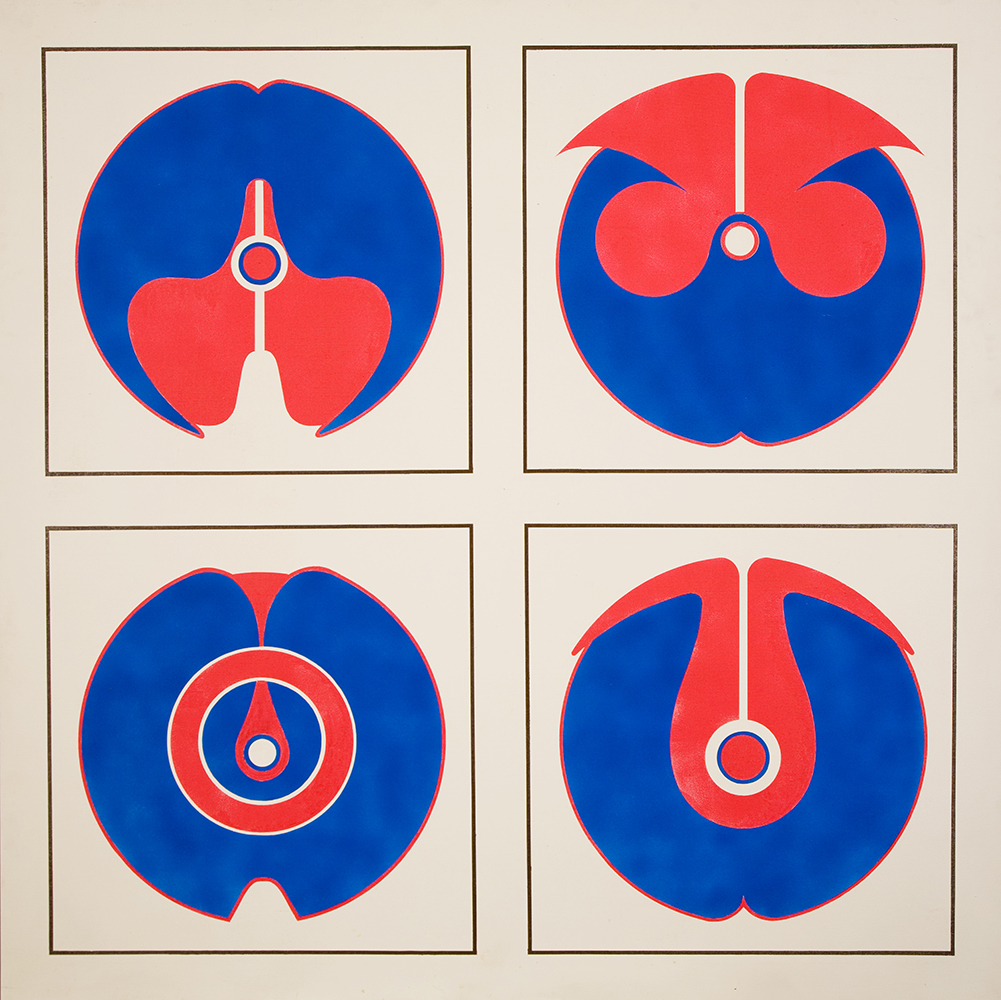

Richard Taylor studied art at the University of Utah, graduating with a BFA in the late 1960s, acquiring skills in painting, sculpture, photography, and graphic design. The bright colors and sinuous curves in this untitled piece follow similar patterns to those appearing in the spectacular light shows Taylor designed to accompany musical performances in Salt Lake City and beyond. Taylor’s poster design and multi-media production were in demand following the artist’s schooling. He founded Rainbow Jam, a concert production and graphics company, alongside Kenvin Lyman, producing visual effects for bands like the Grateful Dead, Led Zeppelin, Santana, and Jethro Tull. Taylor continued to experiment with emerging technologies, working later in film as a director of special effects for Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Looker, and Walt Disney’s Tron.

People were coming out of a pig’s mouth, romping about in plastic [with] a 30 x 60 foot balloon which contained the band. The balloon was kept up with an air pump, until persons started punching holes in it. Chicks from the Department of Dance were passing around incense and had their faces and bodies painted. They painted other persons whether they liked it or not.

– Jo-Ann Wong, “Up River trip,” Utah Daily Chronicle, May 1970

Best known for his video works, Salt Lake City-born Paul McCarthy studied art both at Weber State University and the University of Utah before furthering his education at the University of Southern California. While at the U, McCarthy was part of the Up River School, a loosely organized group of students from the Art and Architecture departments. Alternatively known as the Upriver Skool and Gum Gum Productions, the group’s most memorable event, The Big Gig, took place on April 29, 1970, in the Union Ballroom. The participatory, multi-media production featured a light show, dance performances, multiple bands, “toys,” and a 17-foot sculpture of a pig that allowed participants to emerge from its playground slide mouth, thus creating psychedelic, immersive environment well-suited for the youth counterculture movements on campus.

Patrick Maguire, “Too Kool for Skool: Paul McCarthy’s Upriver Education,” unpublished manuscript, University of Utah, 2013.

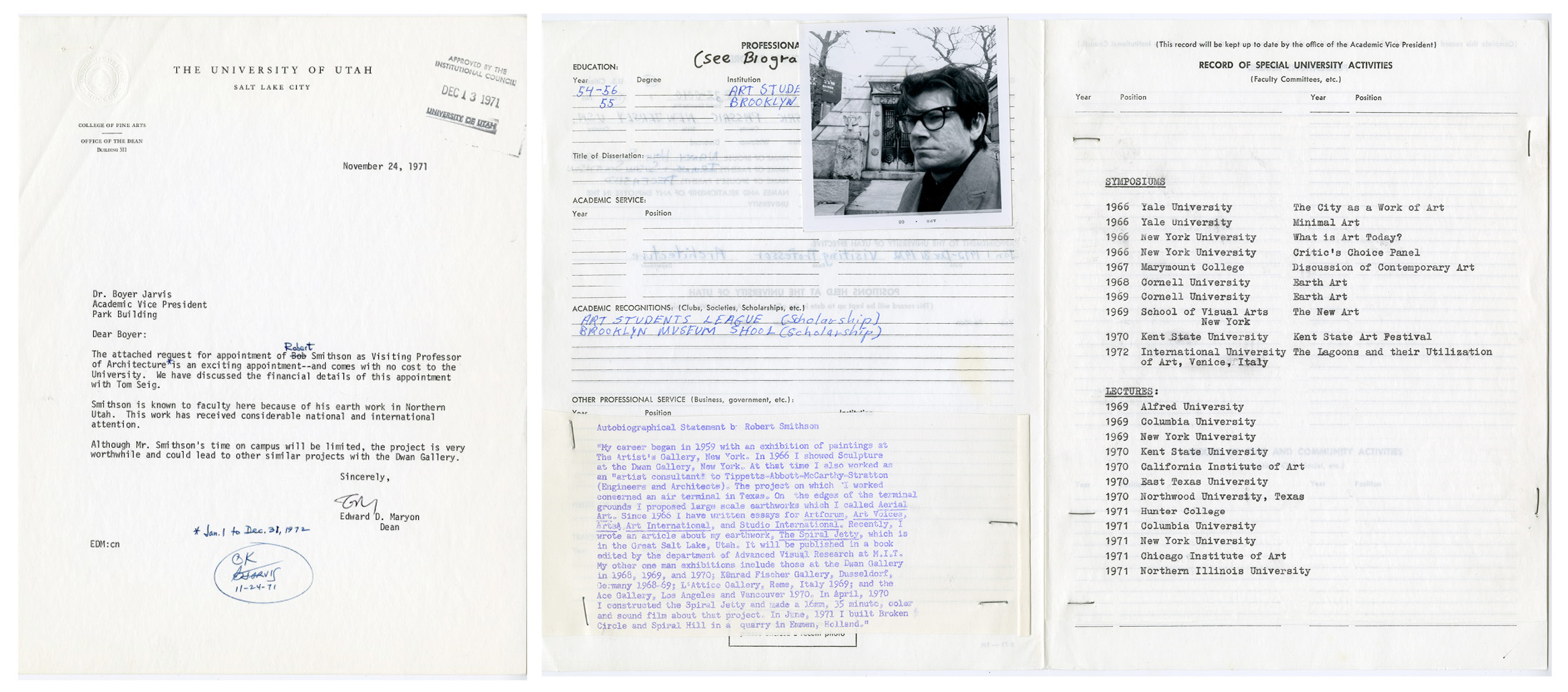

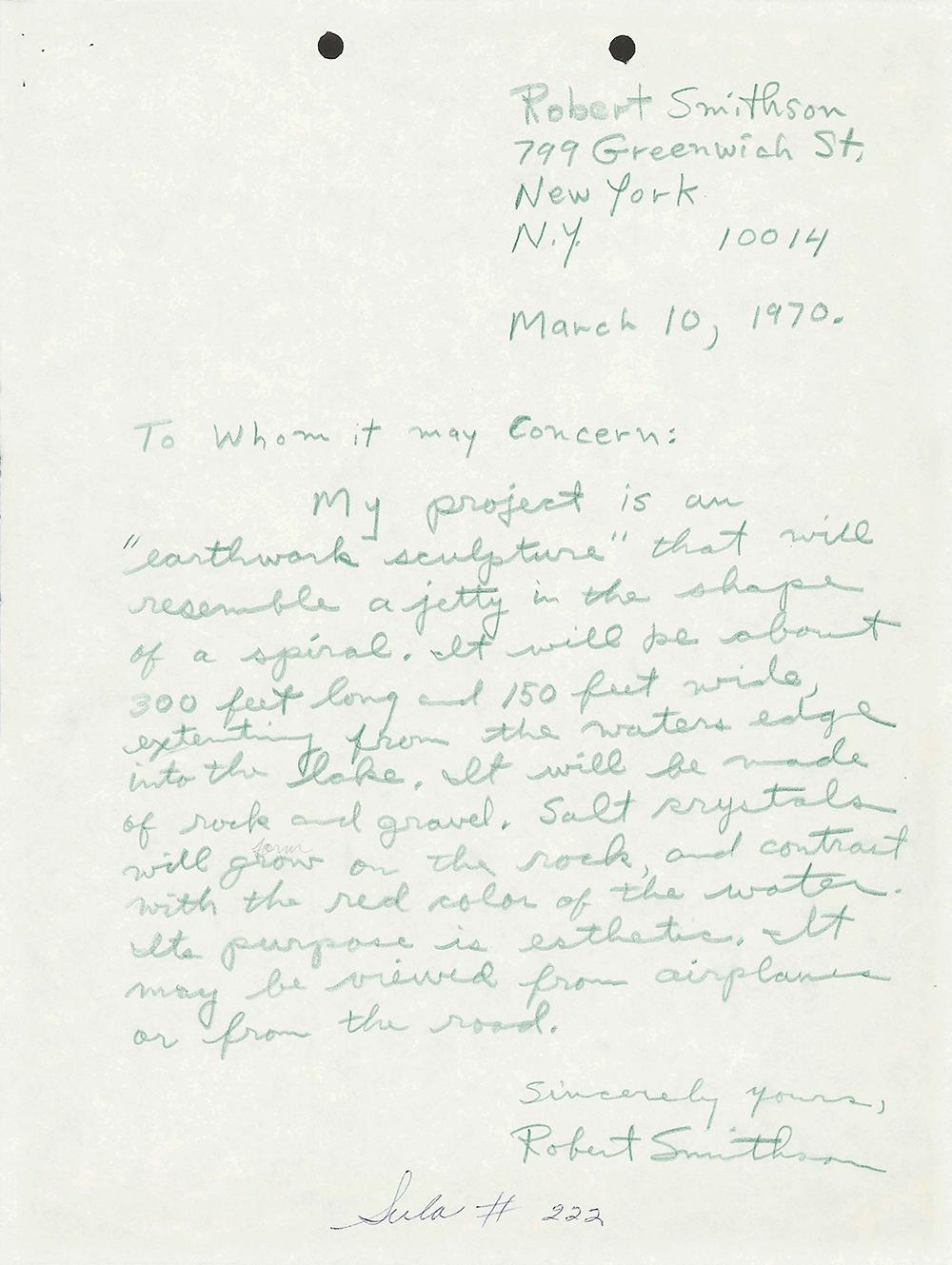

Robert Smithson discussed the possibility of a professorship at the University of Utah with Robert Bliss, then Dean of the School of Architecture, when the two met at a gathering at Spiral Jetty in 1971. A few artifacts and Smithson’s now-legendary Hotel Palenque talk testify to the artist’s fleeting presence on campus the following year. Part lecture, part slide show, Smithson delivered Hotel Palenque in the Fine Arts Auditorium on January 24, 1972 to an audience of around 250 people, mostly U of U faculty and students from the Department of Architecture.

By the time Smithson was appointed his visiting faculty position at the University of Utah,Spiral Jettyhad achieved international fame as an important example of Earth art, however, it was also the subject of an essay and a film by the artist. The documents shown above, dated to coincide with Smithson's professorship at the U, indicate that the artist was scheduled to deliver commentary on the film after a screening at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts.

Whether Smithson was present for the Spiral Jetty screening in the Museum's auditorium, however, remains something of an enigma. Researchers have yet to collect any eyewitness accounts confirming whether the lecture on May 14, 1972, took place as scheduled.Nevertheless, Bob Phillips, the foreman overseeing the construction ofSpiral Jetty, tells us that Smithson screened the film in a far less refined local venue: the Parson Construction Company, where Phillips was employed. Bob Phillips, “Building the Jetty,” in Lynne Cooke and Karen Kelly, eds. Robert Smithson: Spiral Jetty (New York, Dia Art Foundation: 2005), 196.

It is easy to imagine that the art-loving audience at the UMFA would have been more receptive to the nonlinear, experimental film than the Ogden-based construction employees, most of whom left, loudly expressing their disdain and bewilderment, before it was over. Smithson, Phillips recounted, seemed wholly unbothered, stating simply, "My work isn't for everybody. Some people don't understand it." We can only speculate whether the audience at the UMFA screening would have asked Smithson some of the same questions as the few Parson employees who managed to finish sitting through the film.

Questions for Closer Looking

What do you notice when you look at pictures of the University buildings that were new in the 1970s? Do they still look modern to you? Do you know of any places in your neighborhood that look similar? Imagine you're time-traveling fifty years into the future: What do you think of architecture that was built in the 2020s?

Both Richard Taylor and Paul McCarthy were art students at the University of Utah around the same time. Can you find any similarities in their artworks shown here?

What do you think it would have been like to have Robert Smithson as your teacher or professor? What kinds of assignments do you think he would give?

A Complex of Interlocking Forms: Campus Arts and Culture at the University of Utah

Going from Void to Void: Growing the UMFA

Utah on a Turning Globe: Campus of Discontents

A Limited Closed System: Science, Technology, and the First Earth Day

The Will to Respond: Arts and Culture Answer Back

Time Trip Resources