Alana Wolf, collections research curator

This blog post originated in a moment of frustration—as writing so often does—while completing the last of the labels that describe the artworks appearing in Utah Women Working for Better Days!, a new ACME Lab exhibition at the UMFA. The exhibition was prompted in part by an event that happened 150 years ago, when Seraph Young became the first woman in the modern United States to cast a ballot in Salt Lake City. The specifics of my frustration, admittedly narrow, reflect a larger conundrum that curators and other researchers repeatedly encounter: namely, how to handle the contents of an incomplete story.

Utah Women Working for Better Days! is the result of a collaboration with community partners Better Days 2020 and the Landscape, Land Art, and the American West initiative between the UMFA and the University of Utah’s J. Willard Marriott Library, which is funded in part by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Better Days 2020’s goal is to speak to the relevance of Utah women’s contributions of the past and inspire voter participation in the present and future, while the Mellon initiative aims to deepen collaboration between the institutions and draw connections between their collections.

I would like to share three takeaways I arrived at in the yearlong process of organizing this exhibition; some may be less-than-obvious, even to ACME Lab visitors:

- Utah’s suffrage history is far less straightforward than it might appear on the surface.

- Our team spent a great deal of time thinking about multiple pathways to social change; it was crucial that the exhibition recognized methods of civic participation outside of voting.

- The exhibition exposed gaps in the UMFA collection, revealing how institutions such as museums reflect both historic and ongoing systemic inequities. And herein lies the aforementioned frustration.

Suffrage When? And for Whom?

My colleagues residing outside of Utah near-unanimously express surprise when I tell them about the sesquicentennial of Utah women’s suffrage. “Wow, that early?!,” they exclaim, usually followed with something along the lines of, “I didn’t realize Utah was so progressive.” I’m then forced to tell them, well . . . it’s complicated.

The drama of Utah women’s suffrage is knottier than can be unspooled in this blog post; I strongly recommend you take the time to read Better Days 2020’s very accessible take on it. Two facets of the story, however, stand out. The first is that Utah’s early suffrage laws only enfranchised certain women. Native American and Black women living in Utah would have to wait much longer to exercise their right to cast ballots. So it is more correct to say that 2020 is the sesquicentennial of some Utah women’s suffrage, much as the passage of the 19th amendment granted voting rights only to American’s white women.

The second notable point is that the U.S. Congress moved to disenfranchise Utah women seventeen years after the state had granted them the vote. It was part of a larger Congressional order outlawing polygamy in the state, among other things, however, it was the only time in U.S. history that Congress voted to remove voting rights from any group.

Suffrage, then, was not something granted to all Utah women in a single act, but was fought for, rescinded, and reclaimed at different times for different groups.

The fact that legislation—like public sentiment—is never static but always in the process of being shaped feels especially relevant right now.

Beyond the Vote

Beyond the various voting rights anniversaries taking place in 2020 and our team’s collective interest in that most fundamental of civic activities, we nevertheless hoped that our visitors would regard voting as but one among many methods that Utah women used to create change in their communities. The material we gathered for the exhibition, primarily drawn from the Marriott Library’s Special Collections, recognizes women who worked through official government channels, as well as those who independently organized their own demonstrations, interest groups, and publications. We wanted to emphasize this, in part, to recognize that it was the actions of women who did not yet have the vote that eventually led to legislation which enabled them to participate in the process. Including these alternate methods was also vital because we knew that not every person who visits our gallery would be eligible to vote—but every person can take some kind of action to make change in their communities.

We gathered material in four key areas for action that look beyond the voting booth:

The first action, messaging, highlights Utah women who wrote for and operated newspapers and newsletters, offering examples of media that required substantial overhead compared to today’s social media.

The second action, creating, shows ephemera Utah women created and used in protests that took place more than a century apart, from a nineteenth-century suffrage song book to banners carried in the 2017 Women’s March on Washington.

Contacting includes examples of correspondence to lawmakers, emphasizing constituent influence and encouraging visitors to connect with their own representatives.

Finally, campaigning features material from Utah women who have run for office, suggesting that tomorrow’s elected officials could be the very ones who are visiting our galleries today.

Mind the Gaps

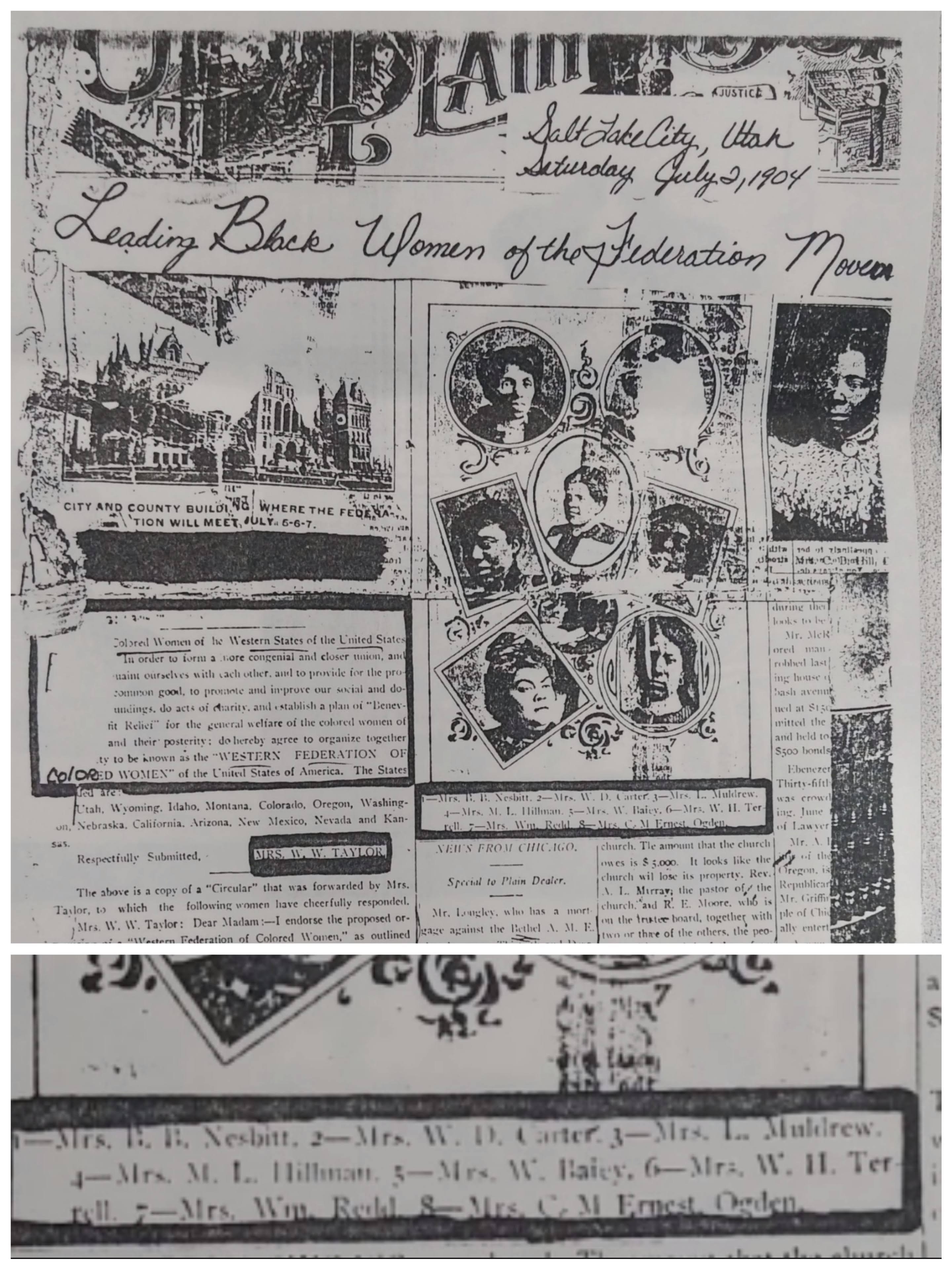

Our team wanted to feature an image from the Utah Plain Dealer in the exhibition, as the newspaper is one of the few extant print records from the turn of the century to chronicle the activities of Utah women of color. However, with the opening date of the exhibition fast approaching, we learned that the image that we’d hoped to use, a portrait of community leader and newspaper publisher Elizabeth Taylor, could not be enlarged to the measurements we need. A frantic search through the Marriott Library’s Special Collections to find a replacement image began to look grim until we came across a reproduction of a 1902 Plain Dealer cover in the Ronald Coleman papers highlighting “Leading Black Women of the Federation Movement.”[1] We were excited to find this story, along with the portraits of the women who participated in the movement. Although it was only a fragment of a photocopy of the paper, it introduced us to a group of women clearly at the forefront of making change in their communities.

We were able to successfully enlarge the collage for the ACME Lab, but my frustration emerged as I began to write the label copy. You’ll notice that in the original newspaper, each of these women is listed by her married name: “Mrs. B. B. Nesbitt, Mrs. L. Muldrew,” and so forth. I wanted to know and share these women’s stories, and the most elementary way to acknowledge them was to include with each of their photos their full given names. Of course, this was not common practice at the time the original images went to press. Nevertheless, through U.S. Census and birth and death records, I was able to acquire some, but not all, of this information; as a compromise, the label is an exact duplicate of the original caption, in quotation marks, appended by the note: “as cited in the Utah Plain Dealer.”[2] Hence, my frustration—that I couldn’t cite these women’s names, much less share their individual stories with our visitors.

My conciliation only highlights the larger hurdles that one often encounters when researching women’s history: even when women’s stories are recorded, they are often buried behind names that are not their own. More importantly, gaps in the historical record likewise reflect the larger hurdle of organizing the exhibition: acquiring content in the first place. The Marriott Library had a surplus of material related to some of our subjects, but our team also hoped to use objects from the UMFA collection to augment the narrative of Utah women manifesting change. But often what is absent from an exhibition is as telling as what is present. I was not frustrated merely with locating an individual’s name. I was frustrated by the limits of collections and how their contents in turn limit the stories we are capable of telling.

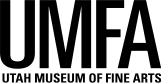

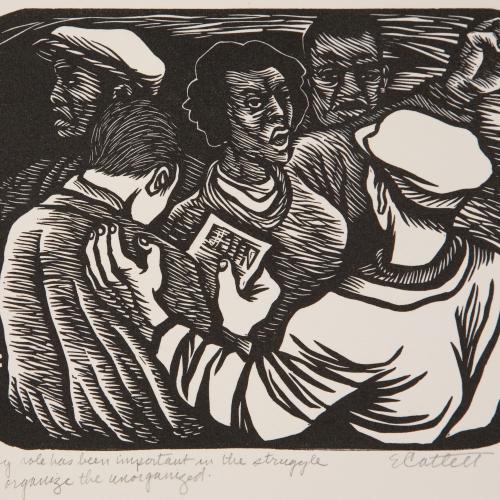

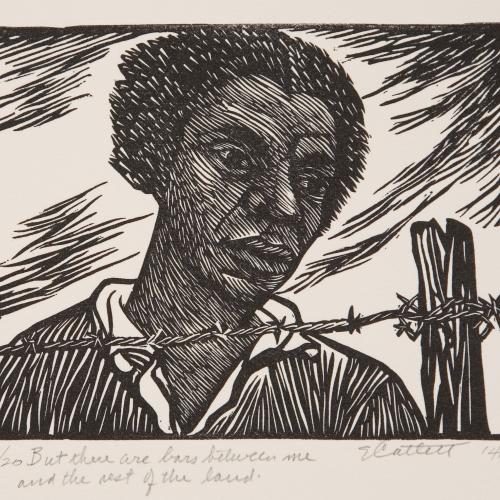

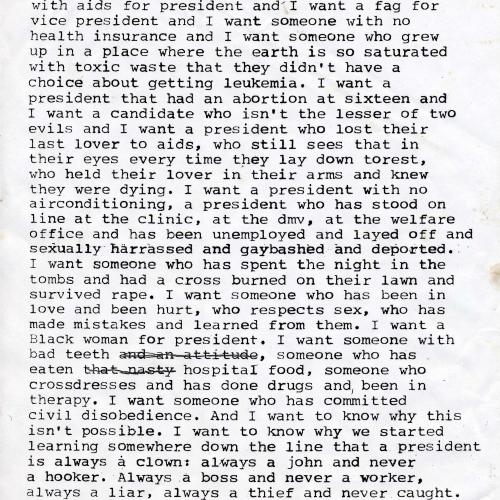

Some of the UMFA’s most powerful images illustrating women’s labor, civic participation, and in particular, the work of women of color could not be included because of the specificity of the exhibition. For example, Elizabeth Catlett’s series of exquisite 1940s woodcuts were ultimately excluded because we were not just looking for the story of women, but of women in Utah. This also meant that Marisol’s Women’s Equality (1975) did not make the cut, despite its direct reference to two well-known figures in the American suffrage movement, nor did Zoe Leonard’s I Want a President (1992), despite its bold declaration of ballot-booth desire.

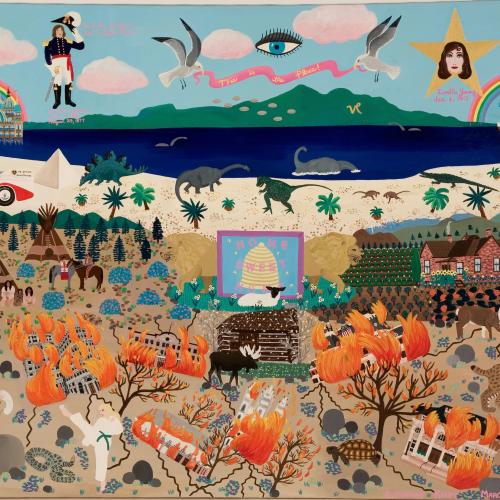

The imagery the UMFA does have of Utah women in the collection, meanwhile, presented different challenges. For example, our team wondered whether visitors might wrongly focus on the prominent buildings engulfed in flames as the call to action in Susannah Kirby’s colorful This is the Place (1990). John Scheffer’s Mrs. Utah Pageant from 1982 ticked a few boxes for our team: it depicts Utah women engaged in a public forum. However, the image not only erases the competitors’ names: it diminishes their individuality quite literally down to a number. In Fred Wright’s photograph from the same year, Republican women gather to hear Orrin Hatch speak in Utah. It’s a perfect time capsule, down to the wood-paneled walls, dizzying plaid carpet, and rows of neatly groomed women with near-identical coiffures, but hanging it in the gallery by itself felt a bit partisan—unlike the Reva Beck Bosone and Ivy Baker Priest campaign material that we borrowed from the Marriott Library, we were unable to locate comparable material at the UMFA that could provide a counterpoint to Wright’s photo, even if indirectly.

The lack of artwork in the UMFA collection that speaks to Utah women’s participation in shaping the state, while both frustrating and sobering, is neither surprising nor unique. Despite the UMFA taking strides to create a museum where everyone belongs, we know that there is still much work to be done. Art museums have historically been erected on deeply homogenous foundations, lacking diversity in both their staffing and in the artists that such institutions collect. The work of changing, which museums around the world have been undertaking for some time, often feels painfully slow.

In a recent first-of-its-kind study, which sought to quantify the demographic diversity of eighteen major art museums in the United States, researchers identified 85.4% of the artists in their collections as white, 9.0% Asian, 2.8% Hispanic/Latinx, 1.2% Black/African American, and 1.5% other ethnicities. Work of Black and Native American women represented less than 1% of all of the art that the museums collected.[3] When broken down by more recent collecting years, these statistics proved more encouraging, yet artist diversity continued to lag behind comparable population demographics. While I have no hard data for the UMFA collection, I would not be surprised if we hold similar numbers, including a visible and encouraging shift from the turn of this century—and especially this past decade—to acquire and present more work by underrepresented artists.

In the countless times our team convened in planning Utah Women Working for Better Days!, our collective hope for the exhibition remained constant: to inspire visitors both to take action in their own communities and to acknowledge the efforts of the women around them—whether or not they appear in a newspaper or on a political platform. Recent events have only reaffirmed my belief that these stories need to be told.

Voting is one action, but our actions do not have to end there. As a society, we are called to do better. Our institution is examining how to answer that call. As we move forward, one answer might be within our own collections.

[1] Ronald Coleman papers, ACCN 1020. Special Collections and Archives. University of Utah, J. Willard Marriott. Salt Lake City, Utah.

[2] This research is ongoing, but paused, as related archival material and notes are physically inaccessible at this time due to COVID-19.

[3] https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0212852. The methodology involved data scraping the institutions’ online catalogs.

Elizabeth Catlett, My role has been important in the struggle to organize the unorganized, from The Black Woman series, 1946-7, reprinted 1989, linoleum print on wove paper, purchased with funds from the M. Bell Rice Fund, UMFA1991.039.009.

Elizabeth Catlett, But there are bars between me and the rest of the land, from The Black Woman series, 1946-7, reprinted 1989, linoleum print on wove paper, purchased with funds from the M. Bell Rice Fund, UMFA119.039.010.

Fred Wright, Hatch Campaign – Utah Republican Women, 1983, gelatin silver process, 9 in. x 12 in., Purchased with funds from the George S. & Dolores Eccles Foundation, UMFA1983.059.

Zoe Leonard, I want a president, 1992, ink on paper, 11 in. x 8 ½ in., Purchased with funds from the Paul L. and Phyllis C. Wattis Fund, UMFA2019.1.1.

John Schaeffer, Mrs. Utah Pageant, 1982, gelatin silver print, 8 7/8 in. x 13 5/8 in., Purchased with funds from the George S. Delores Eccles Foundation, UMFA1983.008.

Susannah Kirby, This is the Place, 1990, acrylic on canvas, 35 ½ in. x 48 in., Gift of John-David Robinson, UMFA1997.14.5.

Marisol (Escobar), Women’s Equality, 1975, lithograph on paper, 41 ½ in. x 29 ¾ in., Gift of Lorillard Kent Bicentennial Portfolio, Purchased with funds from the Associated Students of the University of Utah, UMFA1987.055.021.

Fred Wright, Hatch Campaign – Utah Republican Women, 1983, gelatin silver process, 9 in. x 12 in., Purchased with funds from the George S. & Dolores Eccles Foundation, UMFA1983.059.

Alana Wolf is an art historian pursuing questions about technology, perception, and place. She arrived in Salt Lake City in 2018 as the UMFA’s collections research curator where she works on “Landscape, Land Art and the American West" and is particularly fond of tuxedo cats.