By Alisa McCusker, UMFA senior curator and curator of European and American art

The Utah Museum of Fine Arts is excited to dedicate a new gallery this spring to the art of portraiture, or the representation of a specific person or group of people. The new Portrait Hall, opening March 29, is a special space in that it is focused on a major theme in art history, rather than the geographical and cultural designations used to organize most of the Museum’s galleries. The new Portrait Hall is the second-floor hallway overlooking the Great Hall, a central throughway of the Marcia and John Price Museum Building. Many UMFA visitors transition through this hallway from the first floor to the second floor via the elevator from the lobby and will now be greeted by some of the most beloved paintings and sculptures in the UMFA's collection.

The new use of this long gallery for the UMFA’s Portrait Hall parallels the European tradition of presenting portraits of family in great hallways in their residences. For the aristocracy, recording the family lineage was significant for the passage of titles and the associated rights and wealth that came with those titles. To a lesser extent, Americans continued this tradition of displaying family portraits, although the message of entitlement was less pronounced than in the European context and was supplanted with sentiments of familial endearment and pride.

The selection of works in the inaugural installation of the Portrait Hall offers an intriguing cross-section of portraiture from the 16th to the 20th centuries. The sitters in these works reflect the predominance of white European and American patrons, mostly from the aristocratic and wealthy classes, who wished to have themselves depicted in formal portraits. Viewing these works in comparison highlights the complexities of portraits, which contain layers of information beyond appearances and can communicate identities, interests, and even personalities. We can interpret meaning from various aspects of portraits—from more obvious choices of clothing, setting, objects, or symbols to more subtle choices of colors, pose, gaze, and gestures. Each of the works in the new Portrait Hall—from Renaissance to contemporary—offers visitors different ways to consider the significance of self-presentation and self-fashioning throughout the history of portraiture.

The earliest work on view in the new Portrait Hall, Portrait of a Young Man Weaving a Wreath of Flowers (see image) of circa 1540 by the Florentine Pier Francisco Foschi (pronounced fos-kee), exemplifies the importance of symbolism in Italian Renaissance art. Although the name of this young man is now unknown, this portrait contains hints of his identity. He likely was from a noble family because they were able to afford a portrait of him at such a young age. His fine clothes are another indication of his elevated status. The flowers he is weaving into a wreath are important clues to the purpose of this portrait, suggesting it was related to his marital engagement. In European folklore, men in love wore blue cornflowers, also called bachelor’s buttons. Carnations are traditional emblems of love and betrothal, and the two red carnations on the windowsill may signal an impending or confirmed engagement. This portrait may have been sent to the family of a young woman with a marriage proposal for their consideration. In that case, the wreath demonstrates his intentions and earnestness. Alternatively, this portrait may have been commissioned to celebrate his engagement, and he weaves a bridal wreath to signal his coming marriage, an important rite of passage into adulthood and a holy sacrament for Christians. This rich symbolism—or iconography—allows us to speculate about this young man’s identity and life events, even though we no longer know who he was (i).

Another UMFA portrait from about 150 years later also bears symbols attesting to the sitter’s identity, including social status and social connections. Hyacinthe Rigaud’s 1692 portrayal of Marie-Françoise de Bournonville, Madame la Maréchale de Noailles (see image), is essentially a testimony of her family’s service to King Louis XIV (the 14th) of France. Rigaud (pronounced ree-go) was one of the leading portraitists of his generation and a favored painter of Louis XIV; therefore, several members of the French aristocracy highly sought Rigaud for their own portraits. French noblewoman Marie-Françoise de Bournonville (1656–1748) was the wife of Anne-Jules de Noailles, who was captain of the bodyguard of King Louis XIV and Maréchal de France (Marshal of France), a distinction awarded to generals for military successes. As his wife, Marie-Françoise was called la Maréchale, the feminine form of Maréchal. The vivid blue and gold-embroidered drapery around her shoulders refers to the kingdom of France and its authoritarian king. In Louis XIV’s own portraits by Rigaud (see image), he famously wore brilliant blue fabrics with gold decorations of fleur-de-lis—the iris or sword lily—a centuries-old symbol of the French monarchy (ii).

By commissioning Riguad to paint her likeness and alluding to one of the most important symbols the king employed in his own images, Marie-Françoise declares her allegiance to the crown as well as the preference she received as the Madame la Maréchale de Noailles.

Following European traditions, American artists also used symbolism to create meaningful portraits that emphasize certain aspects of identity. In the case of Benjamin West’s portrait of his wife and eldest son, the painting reveals perhaps more about the artist than it does about his family. West depicted Elizabeth Shewell West and Raphael Lamar West in a tender embrace, using a circular format called a tondo, from the Italian word rotondo meaning round, which was traditionally used for paintings of the Madonna and Child (Mary and Jesus). West even drew inspiration from a specific Italian Renaissance tondo he saw while visiting Florence in 1762: Madonna della Seggiola (Madonna of the Chair) by Raphael Sanzio.

In doing so, West demonstrates his esteem for his artistic hero, after whom he and his wife named their firstborn child. Interestingly, he also confidently compares his own art with Raphael’s, asserting himself as an inheritor of the Renaissance master’s monumental legacy. West painted this subject at least four times and selected the largest version now in the UMFA for exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1770. West made a bold statement with this seemingly simple, charming portrait of his wife and son by reminding his peers and admirers of his accomplishments.

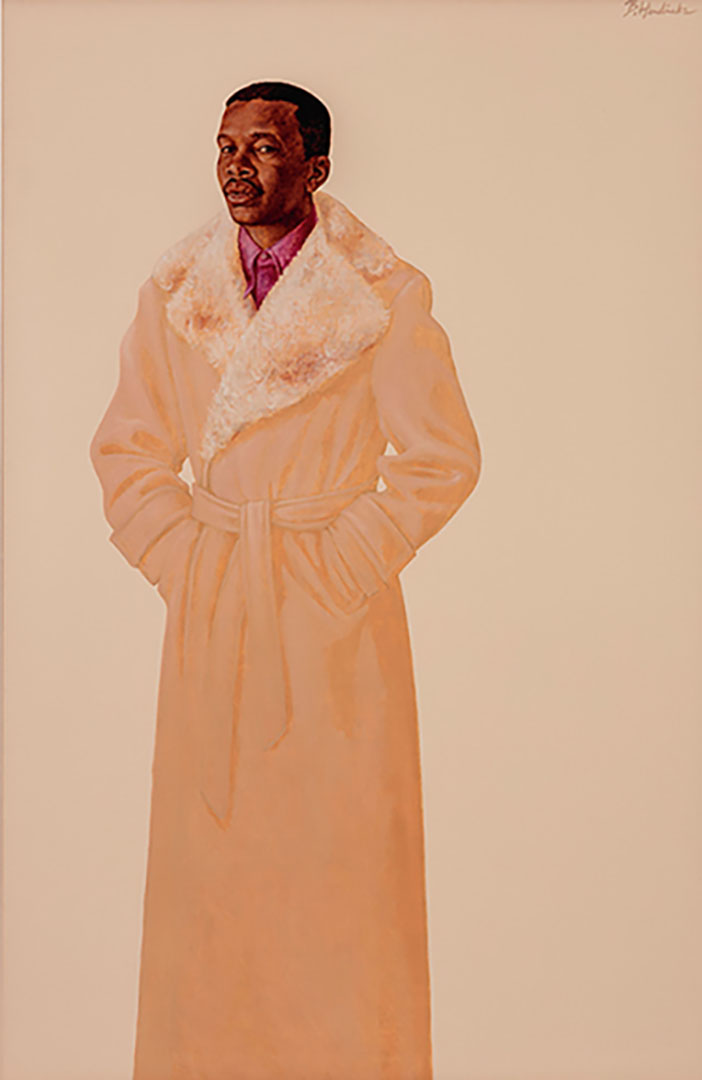

Throughout its first year, the UMFA's new Portrait Hall will prominently feature an important painting that brings tradition into our age. Until March 2026, the Museum is borrowing Barkley L. Hendricks’ stunning, life-size portrait from 1975 of William Corbett from Art Bridges Foundation. Visitors encounter this impressive figure as they exit the elevator from the lobby onto the second floor. Like the historical portraits on view with him, William Corbett gazes out confidently at the viewer and wears fashionable clothing distinctive of his time. He demonstrates his worldliness by wearing a full-length tan coat with an extra-wide, fur-lined lapel. We can recognize the spot-on representation of seventies trends, even if we only pick up on a vibe. Standing like a statue with the sculptural waves and folds of his coat defining his form, William Corbett becomes a monument. His confidence and swagger are reflected in the title he gave his own image, using Black American slang to signal his origin in North Philadelphia and his identity as a cool Black man. Hendricks’ portrayal of Corbett also alludes to perseverance. The artist and sitter grew up in the same neighborhood in North Philadelphia, but their paths diverged in their youth. While Hendricks was studying art at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Corbett was incarcerated for armed robbery. Hendricks painted this portrait after Corbett had served his prison sentence, a testament to redemption after fulfilling his obligation and reclaiming his independent life. Throughout his prolific career, Hendricks significantly updated the history of portraiture by focusing on Black sitters and honoring the Black American experience.

Due to our proximity to William Corbett’s lifetime, we can generally comprehend more about his biography and context than those of the historical sitters from the UMFA’s collection. Deciphering Italian courting and engagement practices, loyalties to the French monarchy, and the ego of an 18th century American artist requires more knowledge than most of us have at the ready. Viewing Barkley Hendricks’ iconic immortalization of his friend amid five centuries of portraiture reminds us that all art was once modern and everyone was once cool.

- (i) For more about floral symbolism in Renaissance art, read Jennifer Meagher’s essay “Botanical Imagery in European Painting” on The Met’s website: https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/botanical-imagery-in-european-painting. For even more, I recommend Celia Fisher’s Flowers of the Renaissance (London: Frances Lincoln, 2011).

-

(ii) For more about the most famous portrait of Louis XIV by Rigaud, visit the Musée du Louvre’s online collection record for it: https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010066115.